The future of Europe’s sixth-generation fighter program seems to be hitting turbulence as Sweden appears to have exited the UK-led Global Combat Air Program (GCAP).

While long assumed, the reported Swedish disinterest pointed towards problems with the other rival projects — France, Germany, and Spain’s Future Combat Air System (FCAS) program.

The development comes amid speculative reports about Germany wanting to quit the FCAS and wanting, ironically, to join the Tempest project. This followed long-running differences with France over the project’s techno-industrial aspects.

Tempest In Turbulence Too

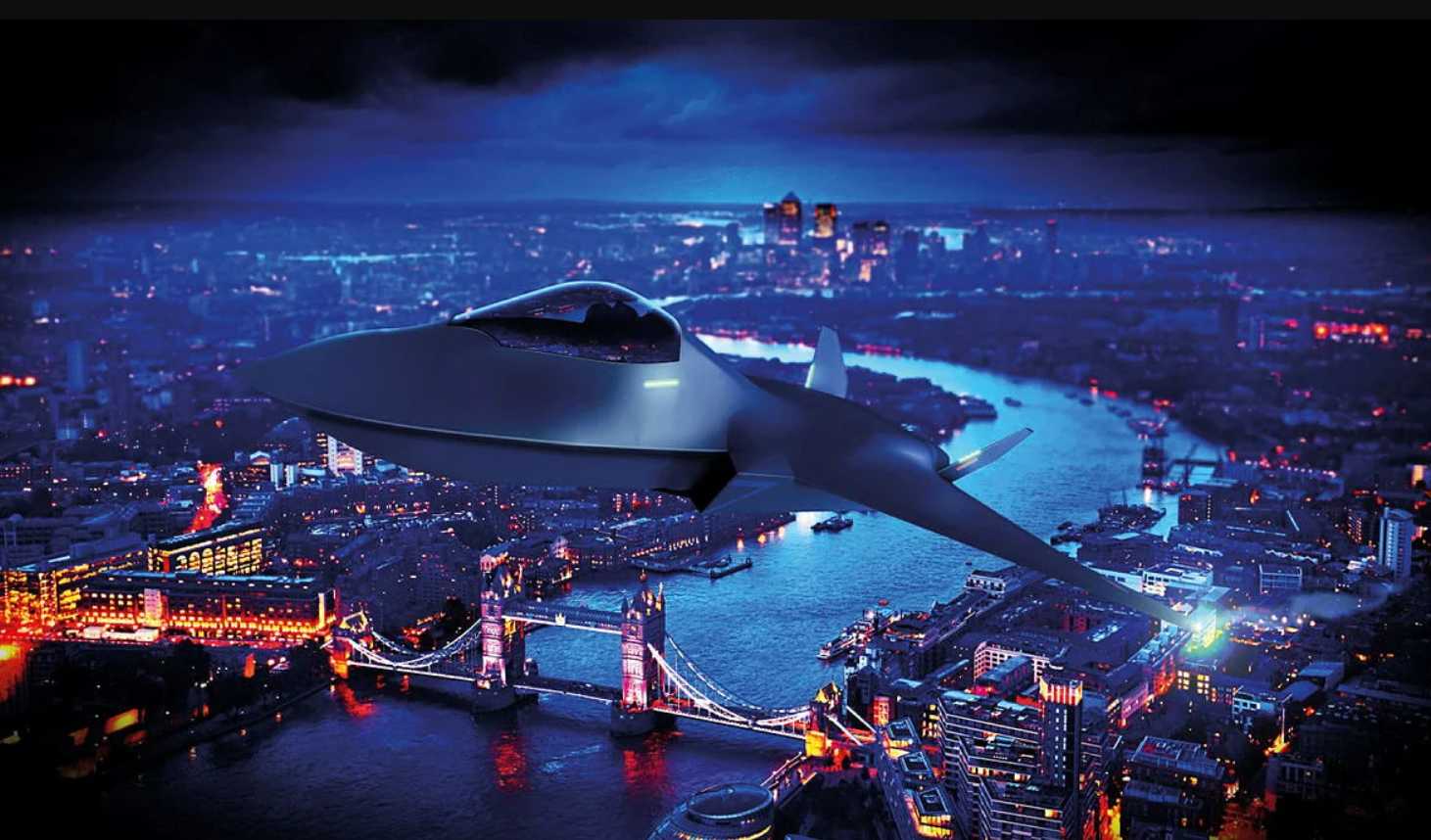

The British-Italian-Swedish collaboration is now unclear, especially since Japan entered the picture. It began with a British-Japanese cooperation in December 2021 to develop engines and radar prototypes for their respective Tempest and F-X fighter projects.

A subsequent announcement in December 2022 unveiled the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) among London, Rome, and Tokyo for a sixth-generation combat aircraft. Sweden presumably dropped out of the project.

The latest statement from a Swedish official at the recently concluded International Fighter Conference 2023 in Madrid gave an official imprimatur to what was long speculated.

Swedish Exit From Tempest Now Official

Defense aerospace journalist Gareth Jennings posted on X (formerly Twitter) on November 7: “Sweden confirms that involvement in Tempest is now officially dead. ‘We walked away from tri-lateral studies with the UK and Italy about a year ago and launched a national study. I will not answer questions about why it didn’t work with the UK and FCAS.’ – official.”

An earlier report on Janes on August 29, 2022, reported how Sweden’s participation in Tempest was “effectively on hiatus.” Saab’s president and CEO, Micael Johansson, said on August 26 that the country is in a “hibernation period” on the multinational project.

Johansson said that the initial promise of the project had not so far materialized and that Sweden’s Saab was taking a back seat while considering the future requirements as other FCAS partners “map out the direction of the program.”

“We are on the margins (of FCAS), and our involvement has not been as intensive as we thought it would be at first. We are not out of the program, but Sweden has hibernated while we see how the UK, Italy, and potentially Japan set up the program. I am not sure how this will play out.”

Sweden joined the UK and Italy on FCAS in July 2019, when the then UK Minister for Defence Procurement in the Ministry of Defence, Stuart Andrew, and Swedish Defence Minister Peter Hultqvist signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to develop future combat aviation technologies jointly.

Although part of the FCAS effort, Sweden focuses on developing technologies to upgrade its domestically produced Saab Gripen fighters. As such, the country has not yet committed to joining the Tempest future fighter project, which is the core element of FCAS.

Even the British, Italian, and Swedish projects shared the same name — FCAS — until Stockholm exited and Tokyo entered the project. Following that, it was called the Global Combat Air Program or GCAP.

German-French-Spanish FCAS Not Smooth Flying Either

Differing French and German visions over the techno-industrial direction and divergent interests had coincidentally marred the French-German-Italian FCAS effort. It was defined by corporate and industrial friction between Airbus and France’s Dassault Aviation over technology and workshare arrangements and a broader and long-running diplomatic rift between Germany and France.

European disunity over collaborative defense projects also afflicted the Sky Shield initiative, which envisaged a standard air defense system protecting Europe. Paris criticized Germany’s inclination towards “off the shelf” systems from nations like the US and Israel.

This undermined France’s efforts to research and develop new-generation air defense systems. On the other hand, the German Chancellery saw France’s approach to its defense industry as overly protective, with little role to play for German defense majors.

Frustration over the lack of progress in the project and the ambiguous timelines — estimated to be around the 2040s — had recently led the Luftwaffe to expect the associated wingmen drones to be ready before the final aircraft.

This followed The Times’ reporting that Germany planned to exit the program instead of joining the Tempest project. However, a section of foreign policy observers believed The Times report to be a carefully planted leak to pressure French diplomatic and defense officials and gain more leverage over the FCAS.

Sweden’s exit is, however, more official and specific and will undoubtedly put the brakes on the Tempest project. The direction of future French and German political ties will decide whether the Tempest progresses with British and Japanese collaboration alone or whether it would need another industrial and advanced engineering major like Germany.

- The author can be reached at satamp@gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News