After nearly eight decades, the US has successfully identified the sunken remains of USS Ommaney Bay (CVE 79), a World War II carrier that was tragically lost near the Philippines in a twin-engine kamikaze aircraft attack.

On July 10, the Underwater Archaeology Branch of the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) announced that it had successfully identified the wreckage site of a World War II US Navy escort carrier.

In a statement, the US military said that the identification of Ommaney Bay was made possible by the collaboration between NHHC’s Underwater Archaeology Branch, the Sea Scan Survey team, and the DPT Scuba dive team.

Combining survey information and video footage confirmed the wreck’s identity, further supported by location data previously provided by Vulcan, LLC (formerly Vulcan, Inc.) to NHHC in 2019.

On January 4, 1945, the USS Ommaney Bay (CVE 79), a Casablanca-class carrier, tragically sank in the Sulu Sea after being hit by a twin-engine suicide plane deployed from Japan.

This devastating attack claimed the lives of approximately 95 sailors aboard the carrier, with two additional casualties on a nearby destroyer who were fatally injured by flying debris.

Ommaney Bay was recognized for its contributions during World War II and was awarded two battle stars for its service.

“Ommaney Bay is the final resting place of American Sailors who made the ultimate sacrifice in defense of their country,” said NHHC Director Samuel J. Cox, US Navy rear admiral (retired).

“This discovery allows the families of those lost some amount of closure and gives us all another chance to remember and honor their service to our nation,” NHHC Director added.

Cox also explained that the absence of any other escort carrier in the vicinity strongly indicated that the identified object was indeed the escort carrier they were searching for.

He said, “Then this latest group was able to get down there and find enough features so that there’s absolutely no doubt.”

Given that the wreck of USS Ommaney Bay serves as the final resting place for the military personnel who lost their lives, any actions that could potentially disrupt the site require authorization from NHHC.

NHHC’s Underwater Archaeology Branch (UAB) assumes a crucial role in establishing policies and overseeing the management of the vast inventory of shipwrecks and aircraft wrecks belonging to the US Navy, encompassing nearly 3,000 ships and over 15,000 aircraft.

With its maritime archaeology and conservation expertise, the UAB conducts extensive research on submerged military vessels, operates a facility dedicated to preserving and analyzing artifacts retrieved from these wrecks, and actively engages in diverse public outreach initiatives, collaborating closely with the diving community.

USS Ommaney Bay (CVE 79)

The USS Ommaney Bay (CVE-79) was an escort aircraft carrier of the United States Navy during World War II. Launched on December 15, 1943, and commissioned in early 1944, the ship played a significant role in various military operations in the Pacific Theater.

Named after Ommaney Bay, an inlet on the eastern coast of Guadalcanal, the carrier participated in some key battles.

The construction of the USS Ommaney Bay began on October 15, 1942, at the Todd Pacific Shipyards in Tacoma, Washington. It belonged to the Casablanca class of escort carriers, smaller than fleet carriers, but played a vital role in supporting amphibious landings and providing air cover during naval operations.

The carrier was 512 feet long, with a displacement of around 10,400 tons and a top speed of 19 knots.

Shortly after its commissioning, the USS Ommaney Bay embarked on a deployment to the Pacific region, serving in the Mariana and Palau Islands campaigns.

During this campaign, the carrier supported the invasion forces and conducted numerous air strikes against Japanese targets.

The carrier also played a crucial role in providing air support during the invasion of Leyte. In October, it participated in the renowned Battle Off Samar, launching fighters that successfully engaged and attacked the Japanese cruiser Mogami, contributing to the overall victory in the battle.

In mid-December, while conducting operations near Mindoro, USS Ommaney Bay narrowly evaded a Japanese kamikaze aircraft attack. However, luck was not on its side during the next encounter.

Less than three weeks later, while traversing the Sulu Sea, the carrier was struck by a twin-engine Japanese suicide plane.

Efforts proved futile despite the proactive measures taken by Captain Howard L. Young, who had ordered additional guards to be stationed on deck as a precaution against potential attacks.

On the evening of January 4, 1945, a lone Japanese Yokosuka P1Y bomber managed to infiltrate the carrier battle group’s escort screen undetected, capitalizing on the sun’s glare for concealment.

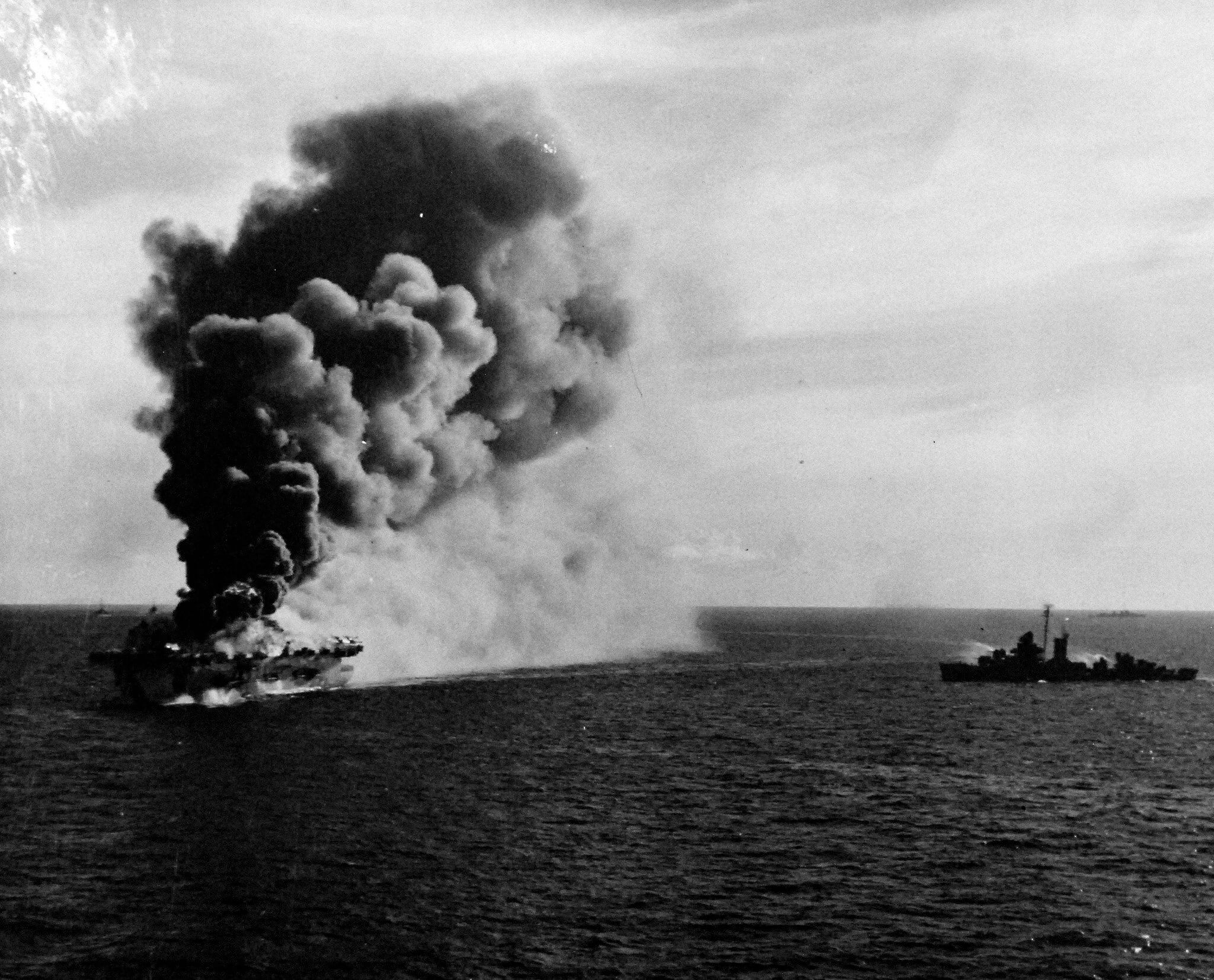

It was too late to mount a meaningful response when Ommaney Bay’s crew realized the imminent danger. At 17:12 hours, the enemy plane released two bombs and crashed into the flight deck.

One bomb penetrated the hangar deck, causing extensive damage to a fire main on the second deck. The other bomb detonated within the hangar, triggering fires that engulfed multiple aircraft.

With the absence of water pressure for hoses and the ammunition detonating within the hangar deck, the fire became uncontrollable, and efforts to extinguish it proved ineffective. As a result, the crew decided to abandon the ship, with the commanding officer being the final person to leave at 18:12 hours.

A mere six minutes later, torpedoes stored at the rear of Ommaney Bay detonated, causing the flight deck to be obliterated and scattering metal debris across the surrounding waters.

Joe Cooper, a sailor who served aboard the Ommaney Bay, vividly recalled the harrowing moments of awaiting rescue in the water after abandoning the ship.

In an account shared with the Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas, he described the desperate scene where men struggled to stay afloat amidst sharks.

He stated, “I remembered we saw a submarine’s periscope from Guadalcanal. We fired a torpedo. I ran back there and saw oil slicks. It was a cargo ship, and they sunk it. It was our first submarine. I’d seen men get pulled under by sharks and eaten up at Guadalcanal. After Guadalcanal, they told us, ‘If you ever hit the water, don’t kick or nothing because the sharks will come after you.”

Cooper followed that advice in the water, remaining still as a few sharks passed by him. He also noted, “No ships came to support us because the light carrier Princeton had been damaged when it went alongside Birmingham when it was bombed, so they stayed away from us. So they let us burn [sic].”

Nonetheless, the USS Ommaney Bay was deemed irreparable and was intentionally sunk by one of its escorts two hours later to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

The attack on USS Ommaney Bay claimed the lives of 95 crew members, including two brave rescuers from the destroyer escort USS Eichenberger, who were struck by debris caused by the blast.

The toll continued to rise as within a week, seven additional crew members from Ommaney Bay lost their lives in kamikaze attacks targeting the cruiser USS Columbia in Lingayen Gulf, off the coast of Luzon.

Recognizing its service, the USS Ommaney Bay was awarded two battle stars for participating in several key battles.

While its time in active service was relatively short, it profoundly impacted the American military’s approach to kamikaze attacks. The lessons learned from the battle led to improved anti-aircraft defenses and tactics to counter the threat posed by kamikaze pilots.

- Contact the author at ashishmichel(at)gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News