An Anglophobic Swedish explorer owing allegiance to Adolf Hilter had sowed the seeds of the border dispute between India and China, a new essay by a former Indian bureaucrat claims.

As Taliban Sweeps Afghanistan, Its ‘Department Of Evil’ Sends Shivers Across The Female Subjects

Apart from the Chinese perfidy that is displayed on the borders with India and in the consequent official interactions involving the serving military officials and diplomats of the two countries, China is also in news in India these days through the books and articles penned by retired Indian administrative service and foreign service personnel.

Two books written by former Indian Foreign Service officers and one major essay authored by a former Indian Administrative Service officer reveal the offensive strategies of China not only on the battlefields but also on the negotiating table. India, they suggest, has not exactly dealt the Chinese offense with the required finesse.

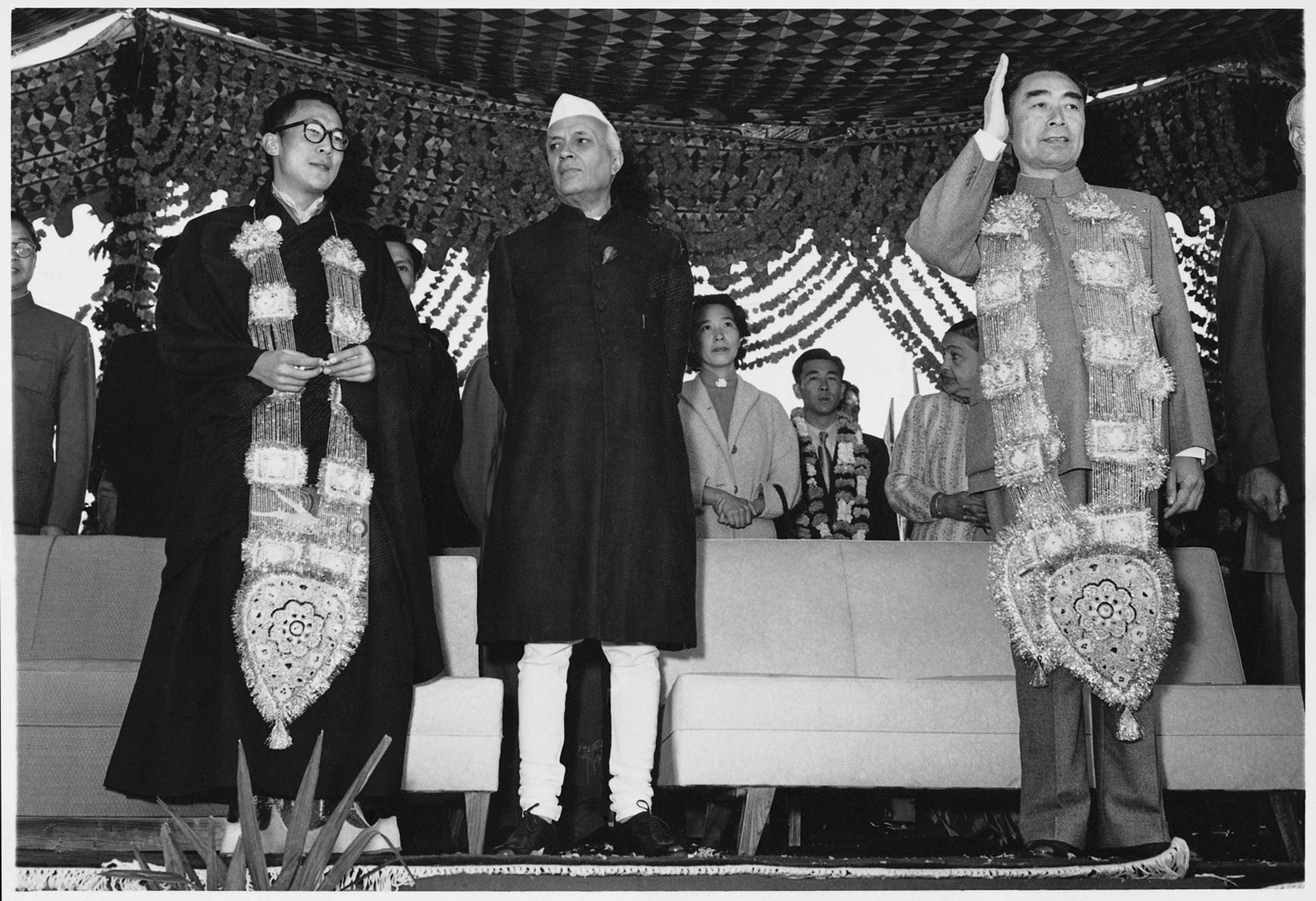

Former Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale’s The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate with India and former Director of the Historical Division in the Ministry of External Affairs, A S Bhasin’s Nehru, Tibet and China give an impression that it was India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s “indulgent approach” towards China that overlooked vital historical factors while negotiating the borders with China.

As a result, India did not argue its case with clarity and assertion, keeping, thereby, the issue alive that subsequently resulted in one major war and a series of clashes and impasses at regular intervals.

Is India Finally Playing The Tibet Card; Using The Dalai Lama As A ‘Strategic Weapon’ Against China?

A New Insight

Former IAS officer Sunil Khatri’s long essay in the latest issue of Strategic Analysis, the flagship publication of the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, offers an interesting angle to the Chinese border claims. Titled ‘Chinese Territorial Claims on Indian Territory in the context of its Surveying and Mapping, 1708- 1960’, it says that the Manchu regime which ruled China till 1911 had never made any territorial claim on India.

Things changed when China became a Republic in 1912. During the Republican period (1912-1949) two non-official privately published maps (1920 and 1933) appeared with territorial claims in India.

What is most interesting is that these maps were authored not by any Chinese official but by a foreigner. He was Sven Hedin, “an Anglophobic Swedish explorer with an axe to grind against Britain and India”.

According to Khatri, “the Peoples Republic China’s maps are not based on official maps inherited by it but on the non-official privately published maps”.

After the Manchus conquered Eastern Turkestan between 1757 and 1759 and renamed it as Sinkiang in 1884, it was Great Britain that encouraged the Manchus to extend the boundary of Sinkiang southward up to Kashmir, with the fear that the otherwise Czarist Russia (China’s more powerful competitor in Central Asia) will get a passage (between Kashmir and Sinkiang) to the warm water port to the Arabian sea, despite Maharaja of Kashmir’s objection.

However, the point that Khatri makes is that during the 150-year period from 1761 to 1911, the Manchus had regarded the Kulan Mountains as the southern territorial limit of Sinkiang and never asserted a claim either on behalf of Sinkiang or Tibet to the elevated plains of Aksai Chin and Lingzitang and the valley of the Changehenmo that were viewed as parts of Kashmir, though the British Indian maps did not demarcate the exact boundary lines on the ground or defined in detail from point to point.

Similarly, in the eastern sector, during the 190-year period from 1721 to 1911, the Manchu had regarded the Himalaya Mountains as the southern territorial limit of Tibet, which was depicted accordingly on its maps, Khatri argues. The Manchu did not assert or claim territory on behalf of Tibet south of the Himalayan crest line.

Genesis Of The Border Dispute

However, things changed after China became a Republic under the Kuomintang. It is well-known that the latter did not accept the McMahon line demarcating the border between Tibet and India following the 1914 Simla convention involving the officials of Tibet, China, and India.

And it was under the Kuomintang that the two privately published maps of China for the first time encroached on Aksai Chin, Lingzitang, and the Damchok area of Ladakh by extending the southern territorial limit of Sinkiang and a large tract of India’s northeast frontier, corresponding to the present-day state of Arunachal Pradesh.

And these maps were prepared by Hedin under the Kuomintang tutelage. Despite his pro-German stance during World War I, he managed to woo back Beijing to initiate and conduct the important Sino-Swedish expedition of 1927–33, which located 327 archaeological sites between Manchuria and Xinjiang.

“Hedin’s intent was never in doubt. At Germany’s defeat in 1918, a crestfallen Hedin had identified the English as the enemy of Germanic races, which includes Swedes… Alongside, Hedin could not forgive the coloured heathen Indian soldier for what he believed was a crime committed by him against culture, civilisation and Christendom through his presence on the European soil during W W I”, points out Khatri.

Hitler’s Man Became China’s Hero

In fact, Hedin was a great favorite of Adolf Hitler for his extremist geopolitical views. So much so that his birthday was declared a national holiday in Nazi Germany and Hitler established a Central Asian Institute, attached to the Munich University.

However, all this notwithstanding, Republican China did not assert the territorial claims in India officially. That happened after the Communist take-over of China.

I’ve acquired a large collection related to Sven Hedin’s 1927-1935 China expedition, including contracts, letters, manuscripts, diaries, photographs, reports, receipts and artifacts etc., here are some appetizers: pic.twitter.com/zabqBIHcey

— China in Pictures (@tongbingxue) February 21, 2018

Communist China’s claims, in many ways, were based on the unofficial maps prepared by Hedin. So much so that on his death in 1952, China honored Hedin by having many of his works translated and published, a rare gesture to a foreigner.

Given this background, Khatri finds it perplexing that the evolution of the Sino-Indian boundary alignment has been overlooked in explaining China’s weak case.

Bhasin also makes the same point when he says: “On the crucial subject of the frontiers, which proved the Achilles’ heel, he (Nehru) did not think it necessary to even calibrate and negotiate with China, which had become its contiguous neighbour for the first time in history(after taking over Tibet).”