Senior leaders from more than 40 countries attended the second round of talks in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on August 5 and 6, searching for a framework for peace in Ukraine.

During this two-day summit, similar to the previous one in Copenhagen, the Ukrainian representative again proposed the ten-point Ukrainian peace formula.

Volodymyr Zelensky had initially proposed this during the last G20 conference in the autumn of last year. The formula presented by Kyiv consists of ten key points, which mention nuclear, food, and energy security, releasing prisoners, restoring Ukrainian territorial integrity, withdrawing Russian troops, and preventing the escalation of the conflict.

China’s Selective Presence

China’s presence in the second round of Ukrainian peace talks was considered very significant because it had not attended the first round of peace talks held in June in Copenhagen.

It is interesting to know why China declined to participate in the Copenhagen round but attended the Jeddah meeting.

This created an impression that Beijing intended to play a more active role in peace talks about the Ukrainian logjam. But a closer dissection of China’s attitude will reveal that it has had a different motivation in being at Jeddah with forty other world leaders in an assembly that ostensibly cared for a viable solution to the war in Ukraine. Some Western commentators said, “Simply put, peace wasn’t Beijing’s primary concern.”

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine in February 2022, China has adhered to its neutrality in the war. Beijing did not allow anything to happen that might have forced it to compromise its neutrality. Due to its commitment to a neutral stance, Beijing faced embarrassment in attending the Copenhagen round of Ukraine peace talks in June.

Denmark is a member of NATO. Although NATO is not directly at war with Russia, it provides military hardware to Ukraine besides moral and political support.

In the eyes of the Kremlin, NATO is also responsible for sustaining Ukraine’s resistance. Since Russia was not invited to the Copenhagen meeting, Russia would have taken the Chinese presence in Copenhagen not in good taste.

But the Chinese presence in the Jeddah meeting has a different background and take. Saudi Arabia is not a member of NATO or any other military block that works against the interests of Moscow. It is a leading power in the Global South, which is fast emerging as the most strategic region in times to come.

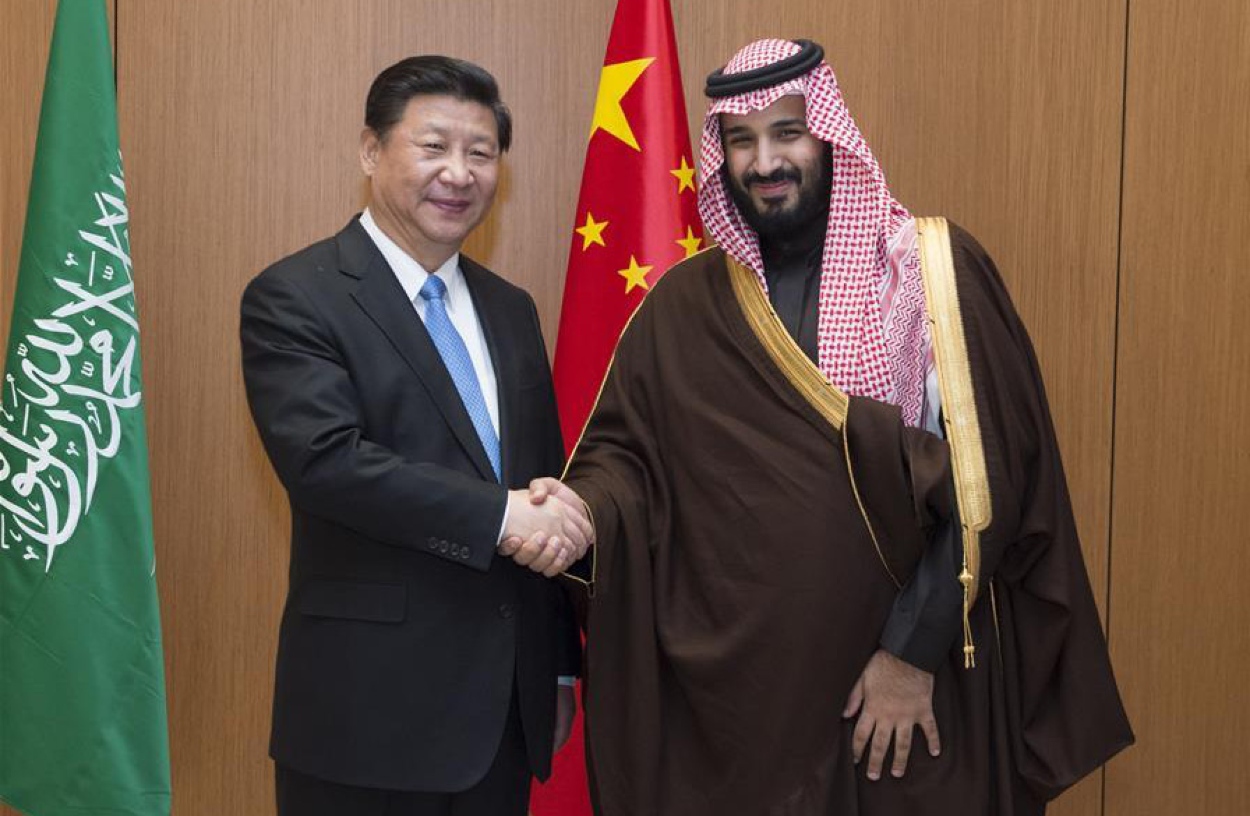

Moreover, only recently, Saudi Arabia recognized its thankfulness to Beijing for mediating peace with Iran. The Saudi crown prince has reposed confidence in the sincerity of China in helping the turbulent Middle East come of conflicts and contradictions that bedevil relations between the nations.

Saudi Arabia has supported several UN General Assembly resolutions condemning Russia and demanding an end to the war. But we should not forget that Saudi Arabia was among a handful of countries that abstained from a 2022 vote to suspend Russia from the UN Human Rights Council. The two countries have developed a mutual understanding of oil production and global crude-oil supply.

Importance Of Sino-Saudi Ties

In attending the Jeddah meeting, Beijing was clear that its interest lay in sweetening China-Saudi relations rather than nursing any intention of condemning Russia for war in Ukraine.

This means China has a long-term vision of cultivating friendship with the oil-rich Gulf States with implications for a new assessment of the entire Middle East.

China and Saudi Arabia have a crucial bilateral relationship driven by “politics, energy, and trade. Saudi Arabia has initiated an effort to bring peace to Ukraine, and the Chinese leaders believe they can endear themselves to the Saudis in their peace effort.

Whether the Saudis succeed or not in bringing peace is a different question, but China would not want to be impervious to the effort made by its friendly Middle East country.

The Jeddah summit did not aim at formulating and signing a pact. Additionally, supposing a consensus was reached in the meeting, neither China nor Saudi Arabia could have imposed their will on Moscow essentially because Moscow was not invited to the meeting. Any consensus opinion would not have the sanctity to be extended to Russia.

It must be noted that the Ukrainian President has been meeting some world leaders with his ten-point peace formula, which Russia has already rejected. No country except the US has endorsed that formula though it remains to be understood that the formula is the brainchild of the American think tanks.

A more insightful view of the situation reveals that a little thaw in the tense US-China relationship facilitated China’s participation in the Jeddah talks.

President Xi Jinping of China will be visiting San Francisco in November. It will be a significant event of the year with far-reaching consequences in Sino-US relations. The two countries are trying to rebuild relations before 2024 when presidential elections will be held in the US and Taiwan.

It is also noticed that China has somewhat supported the West in squeezing Russia over its conduct in Ukraine. In July last, Beijing imposed new “export control measures” on Chinese drones, parts and technologies, and dual-use supplies Russia had received directly from China “or via subsidiaries in Iran.”

In a thinly veiled criticism of Russia, China urged the resumption of grain exports from Ukraine. Moscow has backed out of the Black Sea grain deal, which had allowed Ukraine to export wheat, barley, and other staples.

Conclusion

Some commentators in the West think China has subtly changed its position on the war. This appears a far-fetched idea as of today. China has not acted in any way that would mean imposing critical damage on Russia.

Beijing is unlikely to abandon Moscow as a strategic partner even if Russia is weakened in Ukraine. China’s goals in the Middle East are partly guided by long-term strategy and, in part, reactive and opportunistic.

- KN Pandita (Padma Shri) is the former Director of the Center of Central Asian Studies at Kashmir University. Views expressed here are of the author’s.

- Mail EurAsian Times at etdesk(at)eurasiantimes.com