The heaviest-ever aerial bombing by the US Air Force occurred nearly 50 years ago when 200 US Air Force (USAF) B-52 bombers dropped over 20,000 tons of bombs on North Vietnam.

Shooting Down A Dozen B-52 Bombers, Meet The Russian Missile That Almost Sparked A US-Russia Nuclear War

Tomahawk Missiles: Japan To Spend Billions On Procuring & Deploying US Navy Missiles To Deter China

This is a story about one of the most brutal and devastating aerial bombardments, called Operation Linebacker II, which seemingly resulted in the signing of the historic Paris Peace Accords on January 27, 1973, between the US government, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), as well as the Republic of South Vietnam (PRG) that represented South Vietnamese communists.

The United States claimed the bombing brought the USSR and China-backed Communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) back to the negotiating table.

However, in Vietnam, the bombing is celebrated as a heroic act of resistance in which the Vietnamese took everything their enemy had and remained standing.

President Nixon Called Upon The USAF To Save The Situation

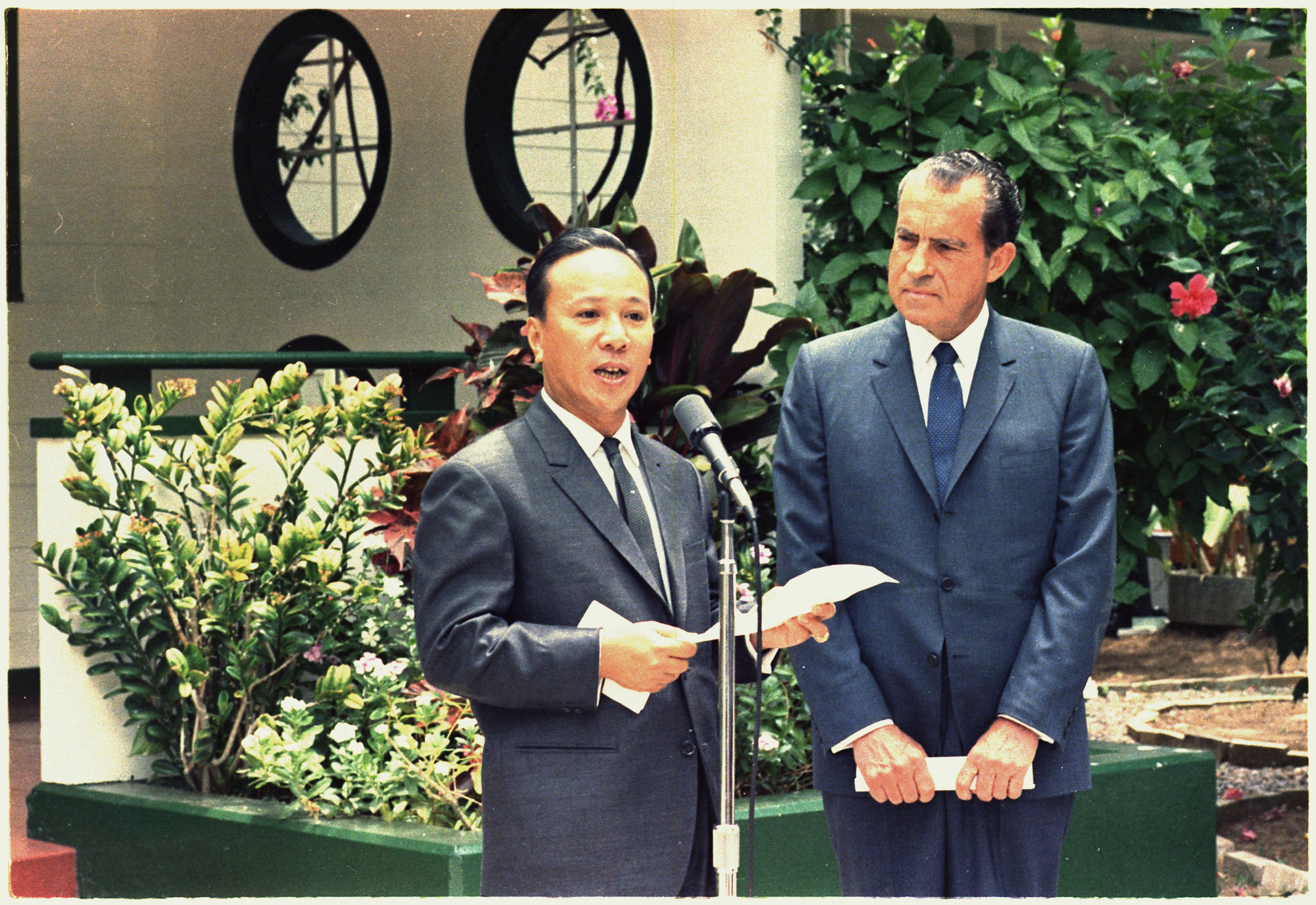

Just over a month before Operation Linebacker II, former US President Richard Nixon had secured a second term of presidency based on a promise to end the American involvement in the Vietnam War that had become very unpopular in the US.

The US had been fighting in Vietnam since 1965. Since 1968, alongside the hostilities, the then US National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese politburo member Lê Đức Thọ were engaged in secret talks in Paris, seeking a negotiated peace.

In the spring of 1972, the DRV launched its largest offensive, the ‘Nguyen Hue’ Offensive (known in the West as the Easter Offensive), in which the North Vietnamese forces almost overran South Vietnam. In response, the US conducted ‘Operation Linebacker,’ an aerial bombing campaign over Hanoi and mining Haiphong Harbor.

Ultimately, the DRV stopped the offensive.

Months later, in October, both sides offered crucial concessions, thereby removing the stumbling blocks which were a cause behind years of stalemate in the peace negotiations.

The US dropped its demand that North Vietnamese forces withdraw from the south, a position that had been implied but not entirely explicit in previous US proposals. At the same time, the DRV abandoned its insistence that the South Vietnamese government headed by President Nguyen Van Thieu must be removed before any peace agreement could be reached.

By October 18, both sides had approved a final draft of an agreement, whose basic terms were a cease-fire in place; the return of POWs; total American withdrawal from South Vietnam; and a National Council of Concord and Reconciliation in South Vietnam to arrange elections, its membership to be one-third neutral, one-third from the existing government in Saigon headed by President Thieu, one-third South Vietnamese communists.

President Nixon was satisfied with the agreement, as it met the conditions for “peace with honor” that he had promised the American citizens during his reelection bid. He sent a cable to North Vietnam’s Prime Minister Pham Van Dong declaring that the agreement “could now be considered complete” and that the United States “could be counted on” to sign it at a formal ceremony on October 31.

However, the US went back on its word after its ally President Thieu, whose government had been completely left out of the negotiations, refused to accept the agreement.

In President Thieu’s view, the agreement amounted to a surrender, as it gave the Communists a legitimate role in the political life of his nation, allowed the Viet Cong to hold on to the territory it controlled in South Vietnam, and permitted the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) to continue its occupation of the two northern provinces and retain more than 150,000 troops in his country.

So, in early December, Kissinger went to Paris to persuade Le Duc Thọ to pull back the NVA troops from South Vietnam, which the latter refused to do while insisting on going through with the agreement finalized in October, and thus the peace negotiations collapsed.

On December 13, Kissinger flew back to Washington to meet President Nixon to discuss the options. One of the proposals by doves in the administration was that the US make a separate deal with Hanoi to release the POWs in return for a total American withdrawal, leaving President Thieu to his fate.

President Nixon did not go for it, as abandoning South Vietnam at that stage, after having shed so much blood, pouring vast sums of money, and so much public outcry that had overwhelmed the American political scene, would be wrong. It would have meant cowardice and betrayal.

Also, abandoning President Thieu would have meant the total defeat of the fundamental objective of the US involvement in the Vietnam War, which was to keep an anti-Communist government in power in Saigon.

Instead, Nixon warned the government in Hanoi of dangerous consequences if it did not return to the negotiating table and called upon the US Air Force (USAF) to save the situation, which it did so by conducting an 11-day strategic bombing campaign called Operation Linebacker II, which later also came to be known by several names such as ‘The December Raids’ and ‘The Christmas Bombings.’

A Massive Blow To B-52 Stratofortress

Before December 1972, the US air campaigns in Vietnam were limited to preventing the overland routes by which North Vietnam was resupplying its forces and Viet Cong forces operating in South Vietnam.

However, Linebacker II was different, as it intended to destroy high-value targets such as vital military installations, railway lines, energy plants, factories, etc., to shake the Vietnamese “to their core,” in the words of the then US National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger.

The USAF employed its legendary B-52 Stratofortress for Linebacker II, which has been a bastion of the USAF’s bomber fleet since it was first introduced in the 1950s during the height of the Cold War. Seventy-six B-52Hs are still in service, with another 12 in reserve storage.

The bomber can carry 32,000 kilograms of nuclear or conventional weapons and fly at high subsonic speeds at altitudes of up to 50,000 feet (15,166.6 meters), beyond the range of naked eyesight, making its attacks both physically and psychologically catastrophic.

“(Nixon) wanted maximum psychological impact on the North Vietnamese, and the B-52 was airpower’s best tool for the job,” TW Beagle wrote in his thesis, dated June 2000, submitted to the faculty of The School of Advanced Airpower Studies, Air University.

However, it was not going to be easy for these B-52s, as what awaited them were the formidable Soviet-made S-75 Dvina (NATO reporting name SA-2 Guideline) high-altitude air defense systems that could fire a 195-kilogram warhead up to altitudes of 30,000 meters at more than Mach 3 speed – 3 times the speed of sound.

North Vietnam had fielded around 26 S-75 surface-to-air missiles (SAM), of which 21 were employed in the Hanoi/Haiphong area, with a heavy concentration of anti-aircraft artillery and a complex, overlapping radar network.

Also, the radar network had secretly been improved by introducing a new fire-control radar (FCR) that is said to have improved the accuracy of the S-75 weapons.

Moreover, the tactics employed by the B-52s had not changed much since World War II, which also proved fatal.

“They’re going to be so god damned surprised,” US President Richard Nixon said to Kissinger on December 17, and the next day, 129 B-52s took off from Guam and Thailand to obliterate the Hanoi and Haiphong areas in North Vietnam, marking the onset of Operation Linebacker II.

The operation continued for the next 11 days, with a respite on Christmas Day to give the USAF planners a chance to review events and provide the bomber crews with some rest.

The North Vietnamese missile gunners downed a total of fifteen B-52s, with six bombers shot down in one night. This was a massive blow to the legendary B-52 Stratofortress and the US Air Force.

Death And Devastation On Both Sides

A total of 33 USAF airmen lost their lives. Since the bombings were conducted at night, and the Bombers that made it back to base would land in darkness, the crew would not realize until the following day who among their colleagues had failed to return.

“You’d see the trailer next to yours with doors open on both ends and airmen loading (the occupant’s) personal belongings into a trunk to be shipped back to their families, so you knew that crew didn’t make it,” Wayne Wallingford, an electronic warfare officer based in U Tapao who flew on seven of the 11 raids B-52s undertook over Hanoi, recalled in an interview with CNN.

“It was pretty sobering to see that,” he said.

Over 12 days, that unpleasant ritual was performed 33 times.

The losses suffered by the USAF were unprecedented, and so was the devastation in Vietnam caused by the B-52s.

According to Vietnam War historian Pierre Asselin’s book, ‘Vietnam’s American War: A History,’ “1600 military installations, miles of railway lines, hundreds of trucks and railway cars, eighty percent of electrical power plants, and countless factories and other structures were taken out of commission.”

At the time, the communist authorities said about 1,600 Vietnamese were killed, however, many believe that the actual figure is much higher.

According to the Vietnamese newspaper VN Express, the bombings resulted in 2,380 civilian deaths, of which 287 people were killed in one night alone in Kham Thien, an area in Hanoi, the majority of which were women, children, and elderly, who did not manage to escape in time.

A bronze statue depicting a young mother carrying her dead child is placed on Kham Thien street in Hanoi as a memorial to all the victims of America’s ‘Christmas Bombings.’ Both died from suffocation under the rubble of a house at 47 Kham Thien, where the statue now stands.

North Vietnamese Did Not Budge!

Ten days following the end of Operation Linebacker II, which was on January 8, 1973, the peace negotiations resumed.

The Americans thought the bombing campaign had forced North Vietnam into submission, but Vietnamese media reports maintain that North Vietnamese negotiators led by Le Duc Tho did not budge even after the devastation brought by 20,000 tons of bombs.

In Hanoi, “the story of the events of late December 1972 was a tale, not of massive loss and destruction, but of heroic resistance by Northerners,” wrote the historian Asselin.

As a result, on January 27, 1973, both sides signed the Paris Peace Accords on terms reached earlier in October 1972.

The terms in the final agreement are more or less the same as the details of the draft agreement finalized in October 1972, which were released by the DRV’s official news agency on October 26, 1972, following the commitment from President Nixon to sign the agreement on October 31, as stated earlier.

This means that Hanoi did not change its position after all!

The accords marked the beginning of the end of the US involvement in the war. Eventually, as it turned out, all Operation Linebacker II achieved was allowing the US a face-saving exit from the Vietnam war.

Three years down the line, with the majority of US forces out of Vietnam and the Communist forces largely replenished, Hanoi launched a large-scale invasion of South Vietnam which led to the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975.

- Contact the author at tanmaykadam700@gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News