Though the United States and the United Kingdom remain committed to Australia in AUKUS, there is now growing recognition that the industrial and political realities in these two countries pose significant hurdles.

The alliance among the three countries does not appear to be in the best shape to realise AUKUS’s ambitious goals, especially its nuclear-powered submarine ambitions.

In fact, there are significant and growing doubts in the minds of many in Australia that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s firm belief in the deal’s feasibility, despite a growing trust deficit with the United States and grave doubts over the British capacity to develop the submarine, will cost Australia dearly.

The estimated $240 billion to $368 billion cost of the AUKUS over three decades is facing scrutiny, as Canberra, under the security pact, continues to pay the agreed sums to Washington and London without anything concrete in return so far.

Reportedly, the U.S. has received just over $4.6 billion to boost submarine building, while another $4.8 billion (£2.4 billion) is earmarked for Rolls-Royce’s UK engine factory over a decade, half of which has to be made by the end of the financial year 2027/28 and the remainder over the rest of the decade to 2032/33. Some payments of this amount have already been made.

Recently, former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull criticised the “lack of honest public discourse on AUKUS,” arguing that it underlies what he saw as Australia’s exploitation under the pact. “I think the UK saw Australia as a rich dummy that will basically subsidise their creaky submarine program,” he told The Saturday Paper, while quoting Paul Keating (another former Australian premier) that when AUKUS was announced, “ there were three leaders of that announcement. There was only one of them paying.’ Our parliament has the most at risk here, but it has been the least curious and the least informed.”

Incidentally, AUKUS was a trilateral security partnership/pact signed in September 2021 by the then Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and U.S. President Joe Biden. It is a trilateral security pact designed to strengthen defense capabilities in the Indo-Pacific, primarily focusing on providing Australia with nuclear-powered submarines.

They announced that this pact would ensure a “free and open Indo-Pacific” by enhancing Australia’s defense capabilities.

AUKUS is said to be structured into two “pillars”:

Pillar 1 deals with “Nuclear-Powered Submarines” through a phased approach. Under this, the U.S. is to sell at least three Virginia-class submarines to Australia in the early 2030s. And the UK will help design a new class of submarine called SSN-AUKUS. It will incorporate advanced U.S. technology and be built in both the UK (Barrow-in-Furness) and Australia (Adelaide).

Pillar 2 envisages “Advanced Capabilities” by developing together cutting-edge technologies, including Artificial Intelligence (AI), Quantum technologies, advanced cyber capabilities, Hypersonic and counter-hypersonic weapons, and Undersea robotics and electronic warfare.

However, despite AUKUS being more than 4 years old, it is highly unlikely that the U.S. will be able to provide any Virginia-class submarine to Australia, as the Americans do not have enough for themselves.

Though President Donald Trump told Prime Minister Albanese during the latter’s visit to the U.S. last October that the AUKUS deal was moving “full steam ahead”, the full details of a Pentagon review into the provision of the promised Virginia-class submarines have yet to be released.

The U.S. has a backlog of 12 Virginia-class submarines, in addition to three Columbia-class ballistic submarines. Its production rates of ~1.2 per year fall far short of the required ~2.33 per year to meet both U.S. and AUKUS needs. Only three U.S. shipyards can build nuclear-powered attack submarines ( Groton, Connecticut; Quonset Point, Rhode Island; and Newport, Virginia). Two of them are functional at the moment, and both are already operating at capacity.

Then there is the American law that makes any transfer of a nuclear submarine to another country conditional on a U.S. presidential certification that the sale will not “degrade U.S. undersea capabilities.”

This is said to be a difficult bar to meet, given the current acute shortage of operational U.S. submarines, even though it is reportedly investing over $17 billion in its submarine industrial base to increase production. Incidentally, Australia is contributing billions to support this effort.

There are similar apprehensions about the British capacity to fulfill the AUKUS obligations, though the UK government’s Strategic Defence Review last June expressed an intent to “double down on both pillars of the AUKUS agreement”.

The country’s submarine capability – reduced since the 1980s – has been described as “shambolic” and “parlous” by a former nuclear submarine commanding officer, retired British rear admiral Philip Mathias.

Apparently, the UK is currently facing a significant shortage of operational submarines due to maintenance delays and a small overall fleet size. While the Royal Navy has 10 nuclear-powered submarines (5 Astute-class attack submarines and 4 Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarines), reports suggest that only about 2 are often ready for deployment. There are significant delays in maintenance and dockyard availability.

Of course, London is firmly committed to the AUKUS partnership, viewing it as essential for long-term security, industrial capacity, and its “Global Britain” strategy. It is said to have invested £6 billion in the last 18 months and signed a 50-year treaty with Australia in July 2025 to secure the partnership.

It is expanding facilities at Barrow and Derby, aiming to construct a new submarine every 18 months. It plans to have its first SSN-AUKUS submarines in service by the late 2030s.

But Mathias is not impressed by all this. “There is a high probability that the U.K. element of AUKUS will fail, making the international row in 2021 over the cancellation of the plan for Australia to build French-designed submarines look like a non-event,” he told The Sydney Morning Herald recently.

According to him, “policy and money don’t build nuclear submarines. People do that, and there are not enough of them with the right level of skills and experience. “

Mathias’s voice is not insignificant. After all, he was in charge of a 2010 review of the UK Trident nuclear-weapons system. And now he says, “It is clear that Australia has shown a great deal of naivety and did not conduct sufficient due diligence on the parlous state of the UK’s nuclear submarine program before signing up to AUKUS – and parting with billions of dollars – which it has already started to do.”

Rear Admiral Peter Briggs, a submarine specialist and past president of the Submarine Institute of Australia, who has tracked the publicised problems with the Royal Navy’s Astute-class nuclear submarine fleet, seems to agree with Mathias. But, he makes another interesting point on the personnel front that sounds worrisome.

Apparently, the UK is having difficulty recruiting the right manpower for its submarine programmes and is being staffed with individuals bereft of meaningful nuclear submarine experience or expertise.

There has been trouble recruiting submarine leadership positions from within the service, and Briggs says the new SSN-AUKUS nuclear submarines are being pushed down the priority list.

“We talk about late ’20s and early ’30s. Fuzzy, fuzzy scheduling already, but even those fuzzy schedules are already slipping,” he says. “And the design review to complete the concept development for SSN-AUKUS is, we’re now told, going to happen in September next year. You’ve then got the detailed design phase.

“There’s no way they’ll be starting to build it in the late ’20s … I guess any day before the 29th of June 2035 is early, but I don’t think there’s any doubt that this will be late, it will be over budget and it’ll have first-of-class issues, and when you’ve got all those problems solved, it is too big for the job that Australia requires it for.”

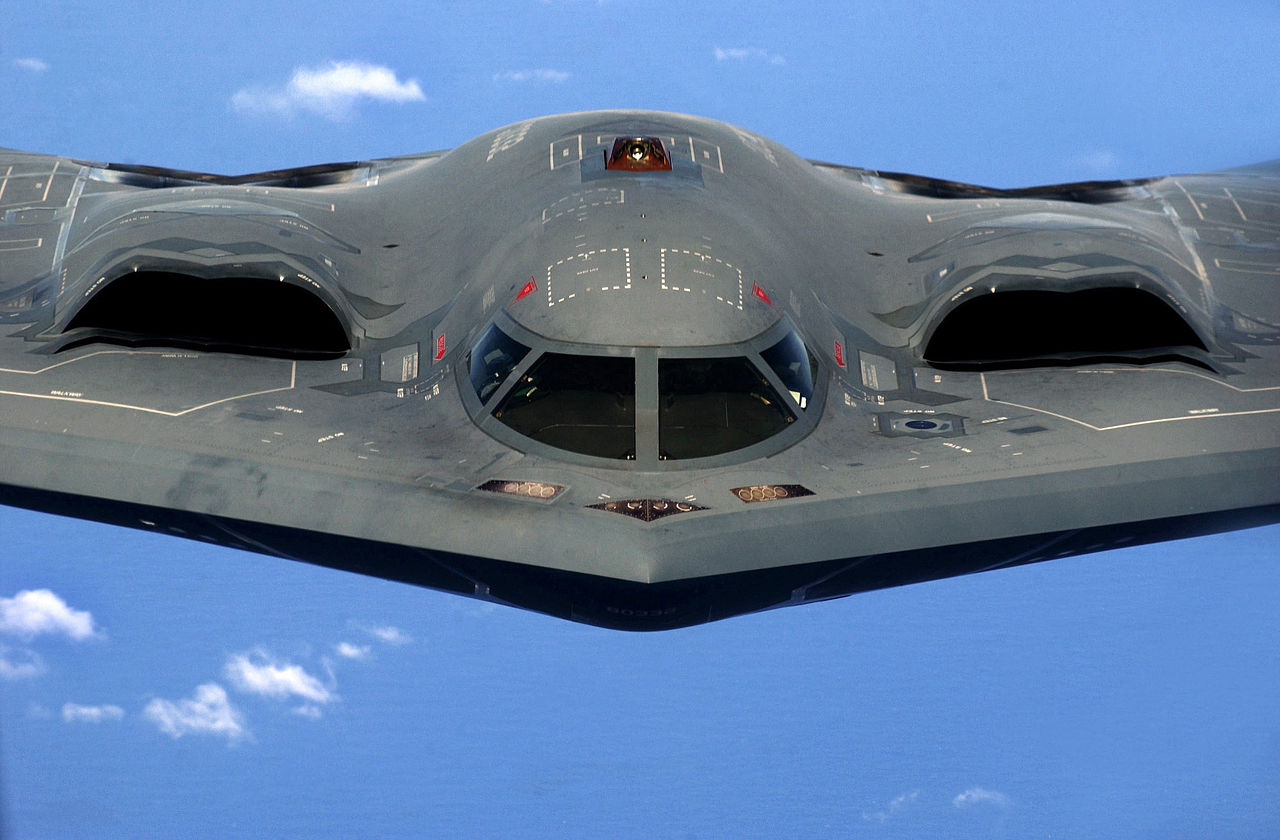

It is against this background of limitations/challenges for both the U.S. and UK in meeting Australia’s submarine needs that some defense experts are talking of “it is time to forget AUKUS submarines for the present and go instead for the B-2 Spirit Stealth Bomber.”

Steve Balestrieri, who served in the U.S. Army Special Forces, argues that transferring retiring B-2 Spirit stealth bombers to Australia would provide a stopgap strategic strike capability. His argument leans on Australia’s lack of a bomber since the F-111’s retirement, and the B-2’s ability to penetrate defended airspace, carry heavy payloads, and reach deep targets with aerial refueling.

A small Australian B-2 fleet could complicate China’s planning by stretching air and missile defenses across the Indo-Pacific, he points out. “The acquisition of B-21s would be cheaper than the AUKUS nuclear submarines and would be able to adapt and react to issues faster than the submarines”.

It remains to be seen if the three partners accept the above idea as an interim measure.

However, at the moment, to prove they remain firmly committed to AUKUS, they have started work on its “second pillar” of technological development.

Construction of the first Deep Space Advanced Radar Capability (DARC) site in Western Australia is underway and expected to be operational by the end of this year.

The three partners have also begun joint trials for quantum-based positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) to reduce reliance on GPS in contested environments.

Besides, a trilateral funding pool of $252 million was established in late 2024 for the Hypersonic Flight Test and Experimentation project, with six testing campaigns scheduled through 2028.

However, the core goal of AUKUS to have nuclear-powered submarines for Australia, its “first pillar,” remains elusive.

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda is Chairman of the Editorial Board of the EurAsian Times and has been commenting on politics, foreign policy, and strategic affairs for nearly three decades. He is a former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and a recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship.

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com