Latin America has been thrust into a geopolitical pressure cooker since Donald Trump’s return to the White House in January 2025, facing a barrage of tariffs, military posturing, and demands to sever ties with rivals like China and Russia.

What began as targeted strikes on alleged drug boats has escalated into a full-spectrum campaign—dubbed the “Trump Doctrine” by supporters and critics alike—to reassert U.S. dominance in “our hemisphere,” as the administration puts it.

From mass deportations of over 500,000 migrants in the first nine months—outsourced to allies like El Salvador—to threats of military intervention in Venezuela and steep tariffs hitting everything from Brazilian coffee to Mexican autos, no corner of the region has escaped unscathed.

The fallout? A Pew Research poll from October 2025 shows 70% of U.S. Latinos disapproving of Trump’s handling of immigration and the economy, with 65% slamming his regional approach—views that echo growing unease across the hemisphere.

“Every Latin American country operates from a position of asymmetry with the United States. That’s the unchangeable baseline,” says Alejandro Frenkel, an international relations professor at Argentina’s San Martín University.

But in Trump’s second term, that baseline has tilted toward coercion, forcing leaders into a stark choice: align, resist, or navigate the gray zone.

Whatever Trump Wants

At one extreme, ideological ally Javier Milei of Argentina “does whatever Trump does and whatever Trump wants,” analyst Michael Shifter of the Inter-American Dialogue think tank in Washington told AFP.

In desperate need of a powerful backer in his efforts to revive a long-ailing economy, Milei has been a vocal Trump cheerleader and has offered US manufacturers preferential access to the Argentine market.

Trump lifted restrictions on Argentine beef imports as part of a reciprocal deal and gave the country a multibillion-dollar lifeline.

Also firmly in the Trump camp is gang-busting President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador — the first country to accept hundreds of migrants expelled under the second Trump administration.

Rights groups said the men were tortured, but Bukele won concessions, including a temporary reprieve for over 200,000 Salvadorans to live and work in the United States and send home much-needed dollar remittances.

In Ecuador, President Daniel Noboa agreed to receive deported migrants and praised Trump’s military deployment and bombing of alleged drug-smuggling boats in the Caribbean and Pacific.

Noboa won closer US cooperation in his own fight against gangs.

Rude & Ignorant

Colombia’s firebrand leftist president, Gustavo Petro, has waged open war on Trump, branding him “rude and ignorant” and—most explosively—comparing him to Adolf Hitler in a blistering UN address.

Petro has repeatedly condemned the U.S. for “extrajudicial executions” after American strikes sank 22 suspected narco-boats and killed more than 80 people, many of them Colombian nationals.

In defiance, he accelerated Colombia’s pivot to Beijing, signing three major Belt and Road deals in a single July weekend.

Washington hit back hard: Trump publicly accused Petro of colluding with drug traffickers, slapped sanctions on senior officials, stripped Bogotá of its status as a key anti-narcotics ally, and—until quietly reversed last month—imposed crippling 50 % tariffs on Colombian coffee and emeralds.

Trump removed Bogota from a list of allies in the fight against narco trafficking. Still, the country escaped harsher punishment — possibly because Washington is awaiting the right’s likely return in the 2026 elections.

Fellow leftist Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of Brazil has also tussled with Trump.

But he is more “pragmatic and firm,” says Oliver Stuenkel, an international relations professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in Sao Paulo.

Lula denounced foreign “interference” after Trump imposed punishing import tariffs on Brazil in retaliation for the coup trial against his right-wing ally Jair Bolsonaro.

Twenty-five years ago, when the United States was its main trading partner, “Brazil would have had to make significant concessions,” said Stuenkel.

But “Brazil now exports more to China than to the United States and Europe combined.”

Silent Diplomacy

Mexico’s new president, Claudia Sheinbaum, has almost no room to maneuver.

More than 80% of her country’s exports flow north, and the USMCA renegotiation is now squarely in Donald Trump’s hands.

Faced with Trump’s threats of airstrikes on cartel labs and blanket tariffs, she has chosen “silent diplomacy”: no public spats, just a surge in intelligence-sharing, record fentanyl seizures, and high-profile kingpin arrests.

So far, the strategy has kept Mexico off the worst of Trump’s tariff hit-list. Yet she drew one red line. When Trump floated unilateral military strikes inside Mexico, Sheinbaum responded coldly that there would be “no subordination” to any foreign power—quietly reminding Washington that cooperation is a two-way street.

Panama’s José Raúl Mulino is walking an equally precarious line. Within weeks of taking office, he bowed to U.S. pressure and pulled Panama out of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

He then green-lit the sale of two strategic Panama Canal ports previously controlled by a Hong Kong conglomerate—ports Trump had openly threatened to “take back” if Panama didn’t act.

For both leaders, survival in Trump’s neighborhood means delivering results fast, swallowing pride in public, and praying the next phone call from Washington brings praise instead of punishment.

No Provocation

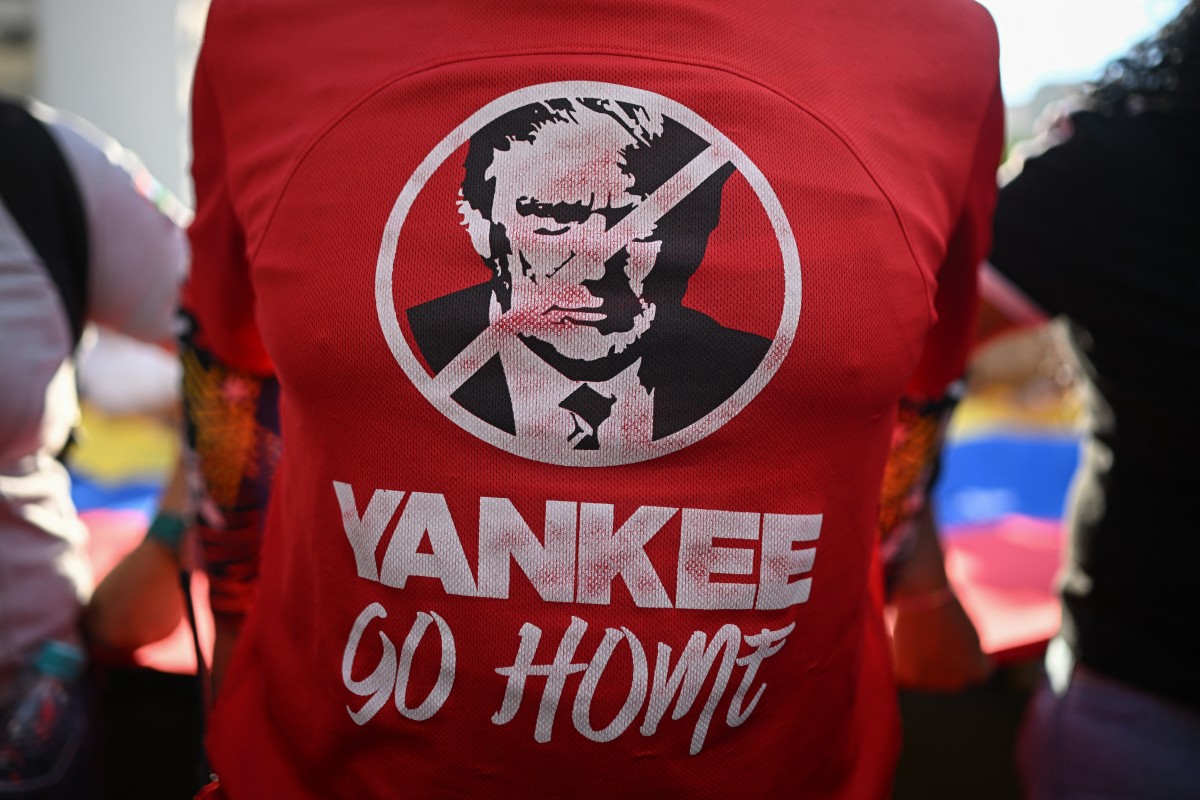

In its own category is Venezuela, which fears that a large-scale US naval deployment in the Caribbean is aimed at ousting President Nicolas Maduro.

The Venezuelan strongman is widely regarded as having stolen two elections and has few allies or economic backers.

Under pressure, Caracas agreed to free American prisoners as Washington allowed Chevron to continue operations in the country with the world’s biggest known oil reserves.

Venezuela has shifted to a readiness posture amid the military buildup.

But the Venezuelans are “trying hard not to provoke the US,” said Guillaume Long, a senior research fellow at the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research and a former Ecuadoran foreign minister.

- By Agence France-Presse

- Edited & Enhanced by EurAsian Times Online Desk