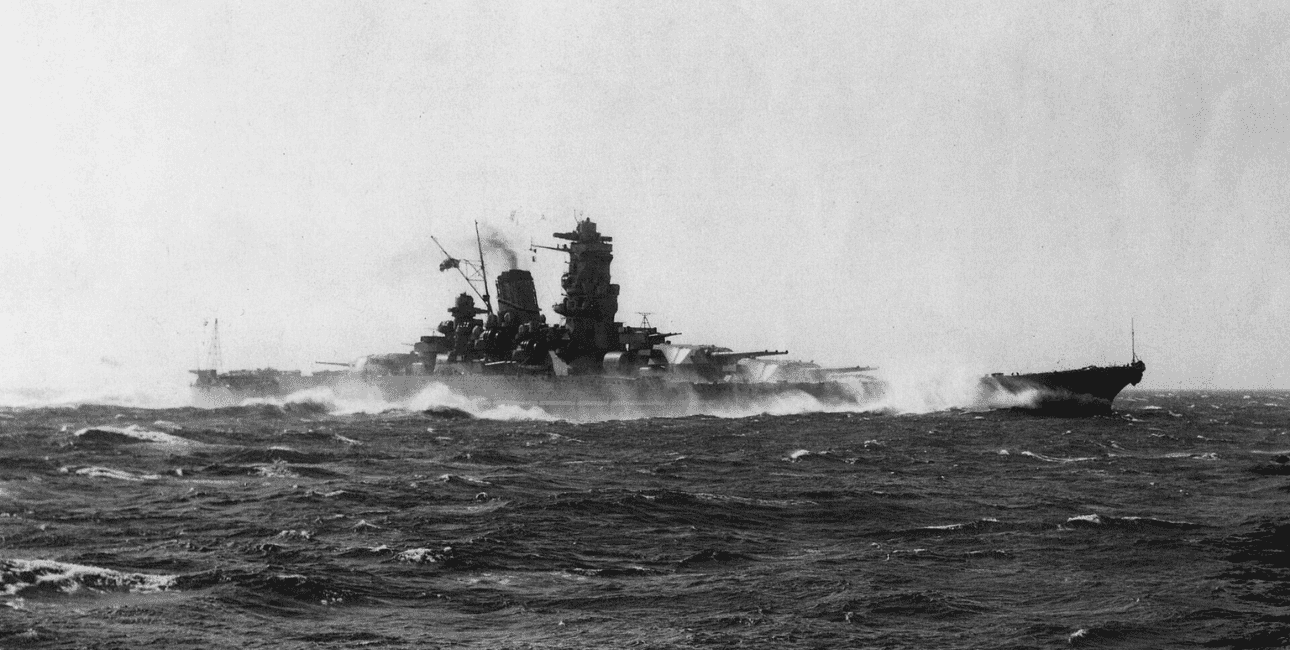

In the final months of World War II, as Japan’s defeat became inevitable, one of its most powerful war machines made a desperate last journey. The Yamato, once the pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy, sailed on a mission from which it was never meant to return.

Her sinking would not only mark the loss of thousands of sailors but also signal the end of the battleship era.

Japan began constructing the Yamato in the 1930s under strict secrecy. The goal was to build the most powerful battleship the world had ever seen—one that could outgun any vessel in the U.S. Navy.

At 863 feet long, she was among the longest battleships ever built. When fully loaded, Yamato displaced nearly 70,000 tons, making her more than 20 percent heavier than the largest Allied battleships.

Commissioned on December 16, 1941, it was the largest battleship ever constructed, embodying Japan’s ambition to command the seas.

But by the end of World War II, the age of battleships had passed. On April 7, 1945, the Yamato was sunk by American aircraft near Okinawa. This event not only marked the fall of a powerful ship but also symbolized the end of Japan’s naval strength and a shift in war at sea.

A Warship Built For Power

The ship had thick armor to protect it from enemy shells and torpedoes. Its guns could hit targets up to 25 miles away.

A second ship, the Musashi, was later built as the Yamato’s sister vessel. Together, they represented Japan’s belief in winning battles through big ships and big guns.

However, the war in the Pacific changed quickly. Aircraft carriers soon became more important than battleships. Planes launched from carriers could attack enemies from far away, beyond the range of battleship guns.

Still, the Yamato remained a symbol of strength. It officially joined the Imperial Japanese Navy in late 1941, but fuel shortages and strategic caution meant it spent much of its early service at port.

Limited Engagements

The Yamato saw little combat during its first years. One of its major missions came in October 1944, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. This was one of the largest naval battles in history. The Yamato fired its main guns during the clash but did not suffer serious damage.

Despite its presence, the battle demonstrated the growing dominance of aircraft carriers. Japan lost many ships and planes in the battle, further weakening its navy. After Leyte Gulf, the Yamato returned to port, waiting for another call to action.

By 1945, Japan was nearing defeat. The United States had captured Iwo Jima in March, putting American forces within striking distance of the Japanese mainland. Meanwhile, U.S. bombers were destroying Tokyo and other cities.

On April 1, the U.S. invaded Okinawa, just 340 miles from Japan. The island was key for launching air raids and preparing for a possible invasion of Japan itself. In response, Japanese leaders launched a last-ditch plan, known as Operation Ten-Go.

Operation Ten-Go: A One-Way Mission

Operation Ten-Go was simple yet desperate. The Yamato would sail to Okinawa and beach itself on the shore. There, it would use its massive guns to fire at U.S. troops. The mission had no return plan.

The ship was equipped with sufficient fuel for a one-way trip. Air cover was minimal—just a few fighter planes would accompany the fleet. Alongside the Yamato were the light cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers. The entire group carried 3,332 sailors, most of whom understood they might not return.

The Yamato left the port of Kure on April 6, 1945. The next day, U.S. scout planes spotted the fleet moving south. American forces acted quickly. Task Force 58, a large group of aircraft carriers, launched more than 300 planes to stop the mission.

The attack began around noon on April 7. Dive bombers dropped explosives from above, torpedo planes struck from the sides, and fighter planes sprayed the decks with gunfire. The Yamato responded with anti-aircraft fire, bringing down a few American planes, but it was no match for the overwhelming assault.

The Yahagi was hit early and sank within an hour. Several destroyers were also sunk or badly damaged. The Yamato managed to stay afloat longer but suffered heavy blows. Torpedoes smashed into its side, and bombs exploded on its decks.

Water flooded the ship. It lost the ability to steer. At around 2:00 p.m., it tilted sharply. A final wave of torpedoes struck, and the ship’s ammunition stores exploded in a massive blast seen from miles away. At 2:23 p.m., the Yamato rolled over and sank.

Out of the more than 3,300 men aboard, only 269 survived. The U.S. lost just 10 aircraft and 12 men. The one-sided battle made clear that the era of battleships had ended.

The Broader Collapse

The loss of the Yamato was a blow to Japan’s already weakened navy. Earlier defeats, like the Battle of Midway in 1942 and the Battle of the Philippine Sea in 1944, had already crippled Japan’s naval power. The Yamato was one of the last major ships remaining. After its sinking, Japan had almost no fleet left.

Meanwhile, the battle for Okinawa continued until June. Over 12,000 U.S. soldiers died in the fighting. Japanese losses were even greater; over 100,000 soldiers and tens of thousands of civilians were killed. The Yamato had been meant to help defend the island, but it never made it.

With Okinawa in American hands, U.S. bombers soon flew from airfields on the island to strike Japan. In August, the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Soviet Union also invaded Japanese-held Manchuria.

On August 15, Japan surrendered. The Yamato’s last mission had been part of this final, desperate phase of the war.

A Symbol Of Change

The Yamato was more than just a warship. Its name originated from ancient Japan and holds a deep cultural significance. For many Japanese, it represented national pride and strength.

The sinking of the Yamato also marked a turning point in how wars were fought at sea. It showed that size and power were no longer enough. Aircraft carriers, with their long-range strike ability, had taken over.

Planes, not guns, now decided naval battles. The Musashi, the Yamato’s sister ship, had already been sunk by planes in 1944. The fate of the Yamato confirmed that battleships had become outdated.

The Yamato’s wreck remained lost until 1985, when it was found 1,000 feet underwater, about 200 miles north of Okinawa. Today, it lies silent on the sea floor, a reminder of a past era and the high cost of war.

The Yamato was built for a kind of battle that no longer existed. Its destruction demonstrated how rapidly technology and tactics had evolved during World War II. While it never fulfilled its intended role, its story remains one of courage, loss, and the shifting tides of history.

In the end, the Yamato became a symbol, not of victory, but of change.

- Via: ET News Desk

- Mail us at: editor (at) eurasiantimes.com