If anything, Russia’s latest test-firing of supersonic missiles from nuclear submarines in the North Pacific implies that Moscow seems to have learnt bitter lessons from the Kursk tragedy of August 12, 2000.

On that fateful day, the Russian nuclear submarine Kursk, while on a naval exercise inside the Arctic Circle, sank to the bottom of the Barents Sea with all hands on board. The entire 118-strong crew perished on the Oscar II-class submarine.

Concluding that the NATO led by the United States is increasingly posing threats to its core national interests, Russia is said to have worked on augmenting the sea-denial power of its Oscar class II submarines (Kursk belonged to this class) by working not only on the modernization of its missiles but also safety culture, rescue readiness, and the human cost of peacetime training risks.

Over the last five years, it has demonstrated this power by reminding the world that its Oscar II submarines still patrol near U.S. and allied waters.

In August 2020, K-186 Omsk surfaced near Alaska during a major Russian exercise. And in June 2024, the Northern Fleet had publicly highlighted cruise-missile launches against sea targets from Orel (an Oscar II) and Severodvinsk (a Yasen-class), with Granit/Kalibr shots at roughly 170 km.

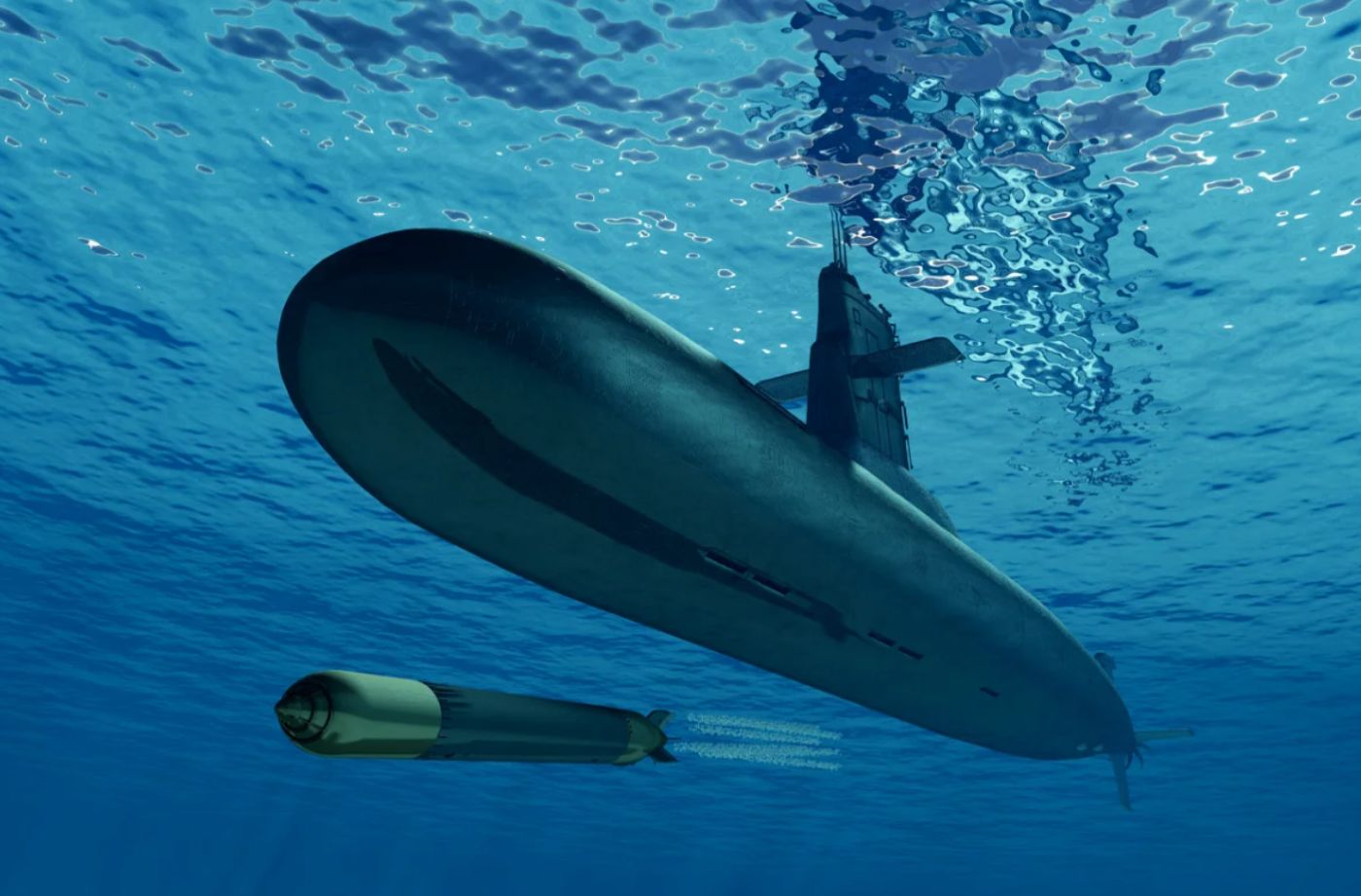

Continuing this trend, a few days ago, September 19 to be specific, Russia’s Oscar II class nuclear-powered submarine, the Omsk, which is under its Pacific Fleet, reportedly conducted a “successful test” of P-700 anti-ship “Granit” supersonic cruise missiles (high speed Mach 2.5+) fired from the Sea of Okhotsk.

Apparently, the missile hit a naval target 250 kilometres away, with two smaller P-800 “Oniks” anti-ship cruise missiles (thigh speed (over 3,000 km/h) being launched against the same set of targets by the Yasen-M class attack submarine, the Krasnoyarsk, as part of the same exercise. All three missiles reportedly hit the targets.

According to a post in the Telegram, Russia’s Pacific Fleet said, “The combat exercises were carried out as part of a command-and-staff exercise with the Joint Command of Forces in the northeast of Russia, aimed at protecting and defending maritime communications in the northern Pacific Ocean, the coast of Kamchatka and Chukotka, as well as the island zone”.

Experts say that the P-700s have been deployed as the primary weapons of Oscar II-class ships since the days of the Cold War. Other weapons systems include 533mm torpedo tubes, 650mm torpedo tubes with Type 86R Vodopad anti-ship cruise missiles, SS-N-19 Granite anti-ship cruise missiles, and mines.

Russia’s financial constraints after the dissolution of the Soviet Union did not allow Moscow much room for upgrading the weapons systems on these submarines until recently. But in the last five years, Russian President Vladimir Putin has attempted to modernize the systems with the introduction of missiles such as Zircon (Hypersonic), Oniks, and Granit.

According to a Federation of American Scientists publication, Russia is in the midst of a decades-long nuclear force modernization program intended to replace Soviet-era missiles, aircraft, and submarines with new systems. As part of this project, Russia’s Navy is currently modernizing its nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) fleet and building new nuclear-powered guided missile submarines (SSGNs), along with other non-strategic nuclear-capable naval systems.

As is the case with every nuclear power, submarines play a key role in Russia’s deterrence strategy, given their stealth and survivability, which enhance second-strike capability. The recent commissioning of new nuclear-powered submarines into the Pacific Fleet is part of a larger modernization campaign as Russia’s older submarines approach the end of their service lives.

Of course, Russia is far behind the U.S. in terms of nuclear-submarine fleets. As of 2025, the US Navy reportedly operates 71 nuclear-powered submarines, making it the largest undersea force. By comparison, the Russian Navy fields fewer than 30 nuclear‑powered submarines.

Be that as it may, if one goes by a report of the Russian news agency Tass, Putin had decided last year that a new division of special-purpose submarines armed with Poseidon nuclear-capable torpedoes would come into operation in the Russian Pacific Fleet by early 2025, and that division would be set up in Kamchatka.

It may be noted that despite the ongoing war in Ukraine, Russia maintains a strong military presence in both the Far East and the Arctic. In fact, on August 21, Russia and China had reportedly conducted what was said to be “Exercise Joint Sea 2025” in response to American “Exercise Northern Edge 2025” in Alaska on August 19.

The U.S. had deployed over 6,400 military personnel, 100 aircraft, and seven U.S. and Canadian vessels, including the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln and three accompanying destroyers, for this military exercise.

However, at the end of August, Russia had also deployed warships to the Far East region near Alaska for what it said was a “patriotic” mission near the area where U.S. and Canadian aircraft and vessels had carried out their operation.

The Russian naval deployment was said to be part of the military’s effort to highlight what it described as “heroism” during the special military operation, Moscow’s term for the invasion of Ukraine.

Besides, as EurAsian Times had explained earlier, Russia is increasingly seeing the whole Arctic coastline – stretching from Norway in Western Europe to the shores of the Aleutian Islands in the Far East – as a continuous strategic domain within reach of its ballistic missiles.

With the ever-increasing melting of ice north of the Bering Strait and expectations of increased civilian and military traffic in the area, Russia has also intensified its military exercises in the region.

Ice-melting in the Arctic has opened up opportunities for Russia that could significantly alter global trade dynamics. The Northern Sea Route (NSR) along Russia’s coast and through the Bering Strait could cut transit times between Asia and Europe by as much as 40%, bypassing traditional routes through the Panama and Suez Canals.

Russia defines the Northern Sea Route as a shipping lane from the Kara Sea to the Pacific Ocean, specifically running along the Russian Arctic coast from the Kara Strait between the Barents Sea and the Kara Sea, along Siberia, to the Bering Strait.

The NSR is expected to give Russia enormous strategic and commercial benefits. For instance, compared to the Suez Canal route, the estimated shipping through the NSR will reduce the distance between Shanghai and Rotterdam (Europe’s largest commercial port in the Netherlands) by almost 2,800 nautical miles or 22 percent. This route will also likely reduce the transportation cost by 30 to 40 percent.

Similarly, while a container ship from Tokyo to Hamburg (Germany’s major port city) sails for about 48 days via the Suez Canal, it can cover the same distance in about 35 days via the NSR.

No wonder the NSR is now the linchpin of Moscow’s new energy strategy. It has constructed ports, terminals, and icebreaker fleets to capitalize on the new shipping routes, enabling the export of oil, LNG, and other resources from the Arctic regions to global markets. Protecting these infrastructures has become a key security concern.

Against this background, the Trump Administration’s desire to acquire Greenland, the regular docking of American submarines in the ports of Iceland over the last two years, the last one by the American Los Angeles-class nuclear submarine USS Newport News at the port of Reykjavik in July, being said to be most significant, has discomforted Moscow.

Above all, Russia is said to have not taken kindly to Finland and Sweden joining the NATO alliance in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Moscow views this as a clear Western challenge to Russia’s traditional dominance in the Arctic region, both militarily and economically. And accordingly, it is choosing its response.

As Mikhail Komin, a fellow at the Centre for European Policy Analysis, argues, “Russia is set to deepen its investment in Arctic civilian and dual-use infrastructure—real spending is already up by 80% over the past three years in addition to the unknown amount of military expenditure. Simultaneously, it is viewing almost every remaining aspect of Arctic policy through a national-security lens, turning previously neutral domains such as climate science and indigenous affairs into instruments of state strategy”.

Moscow is reviving, Komin adds, the Soviet-era “Bastion” concept—remilitarising the Arctic coastline to ensure that air, naval, and ground forces could shield Russia’s nuclear submarines operating in this region. That explains why recent Russian military drills in the region have shown a marked north-eastward shift, away from the Norwegian Sea to the Barents Sea. “These reflect a growing paranoia within the Kremlin about the vulnerability of its Arctic nuclear deterrent”.

In fact, now there is a growing school of thought that the Arctic is no longer “immune from the fires of the Ukraine war”, given the military dimensions of the Russia-NATO rivalry being fully reflected in the resource-rich region.

So much so that Komin fears that “if a direct military confrontation between Russia and Europe does occur—a scenario increasingly entertained by both Russia and NATO—it is unlikely to begin in Poland or Moldova. The more probable flashpoints are in the Barents or Baltic Seas, putting the Nordic and Baltic states on the front line of any future aggression.

“(Russia) is likely to strike first in the Arctic. A ‘pre-emptive’ special military operation would aim to secure strategic assets in the High North. The Kremlin would see securing its Arctic nuclear forces as essential to retaining, as in Ukraine, the upper hand in controlling escalation through the implicit threat of a nuclear strike”.

These are dangerous thoughts, but cannot be wished away.

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda is Chairman of the Editorial Board of the EurAsian Times and has been commenting on politics, foreign policy, and strategic affairs for nearly three decades. He is a former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and a recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship.

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com