OPED by Lt Gen. PR Shankar (Retired)

China places great importance on the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF). It is equivalent to China’s Army, Navy, and Air Force. The PLARF is to enhance its “credible and reliable nuclear deterrence and counterattack capabilities, strengthening intermediate and long-range precision strike forces, and enhancing strategic counter-balance capability.”

The PLARF aims to strengthen China’s capability to “fight and win wars” against a strong enemy (United States?), counter an intervention by a third party, and project power globally.

It is a potent threat to China’s neighbors, especially India. It allows the PLA to influence local, regional, and global military conflicts. The PLARF is a strong and modern rocket cum missile force.

It is the most significant ground-based missile force on Earth. This newly created force is responsible for organizing, manning, training, and equipping China’s strategic land-based nuclear and conventional missile forces and its supporting elements and bases.

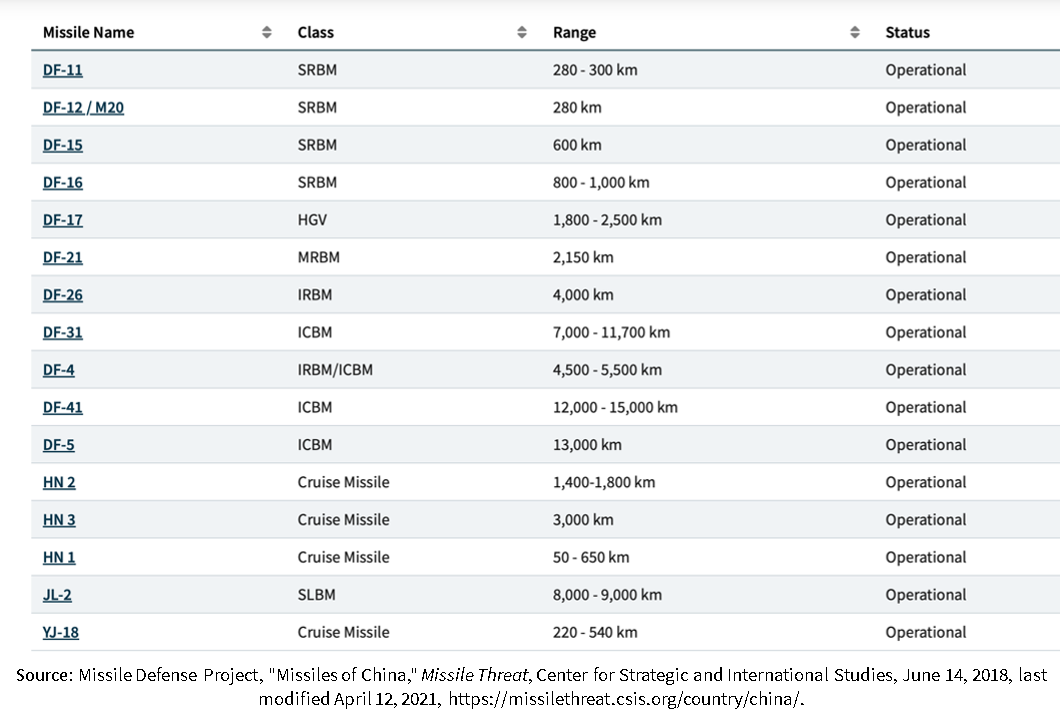

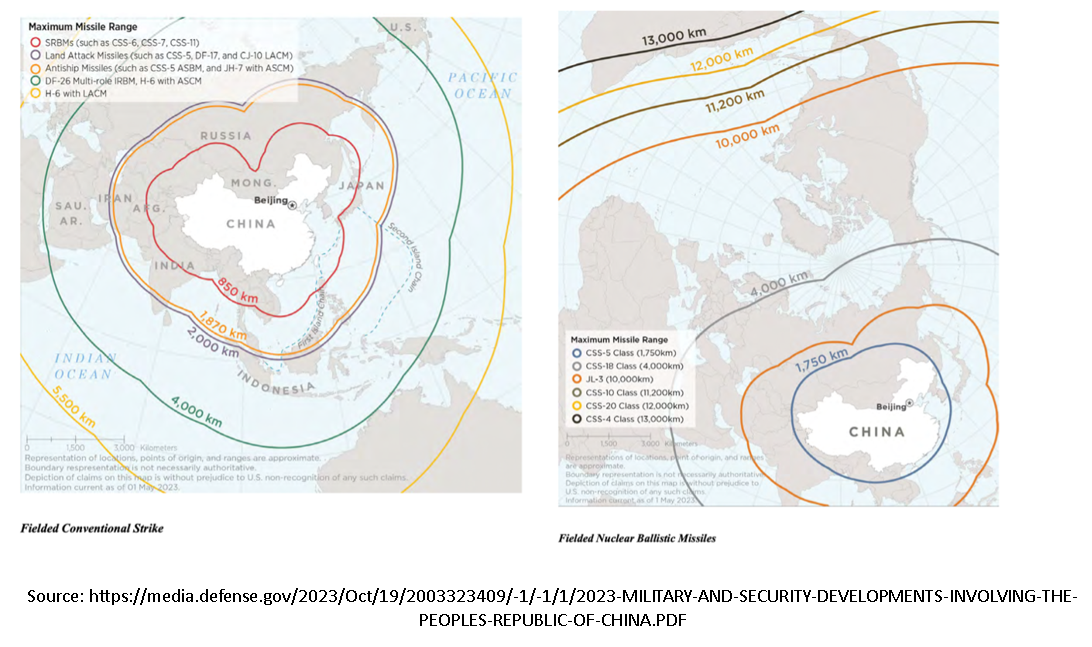

The PLARF has a variety of conventional mobile ground-launched ballistic missiles of short, medium, and long ranges, as tabulated above. It also has ground-launched cruise missiles in its inventory. In addition, it has mobile and silo-based nuclear missiles.

Some of its missile systems, like the DF-26, are dual-purposed and designed to carry conventional and nuclear warheads with precision capability against land and ship targets. All these systems are over and above the air and sea-based missile systems held by PLAF and PLAN.

The PLARF is simultaneously developing and testing newer variants of its missiles and developing capabilities and methods to counter its adversaries’ ballistic missile defense systems. The PLARF is also enhancing the survivability of its storage and delivery systems.

The PRC probably has also established the capability to launch a hypersonic glide vehicle using a fractional orbital bombardment (FOB) system. This much-spoken-of capability has broad strategic implications, whether used with conventional or nuclear warheads. However, it is not a system that is fully developed or deployed as yet. Its capabilities are still futuristic.

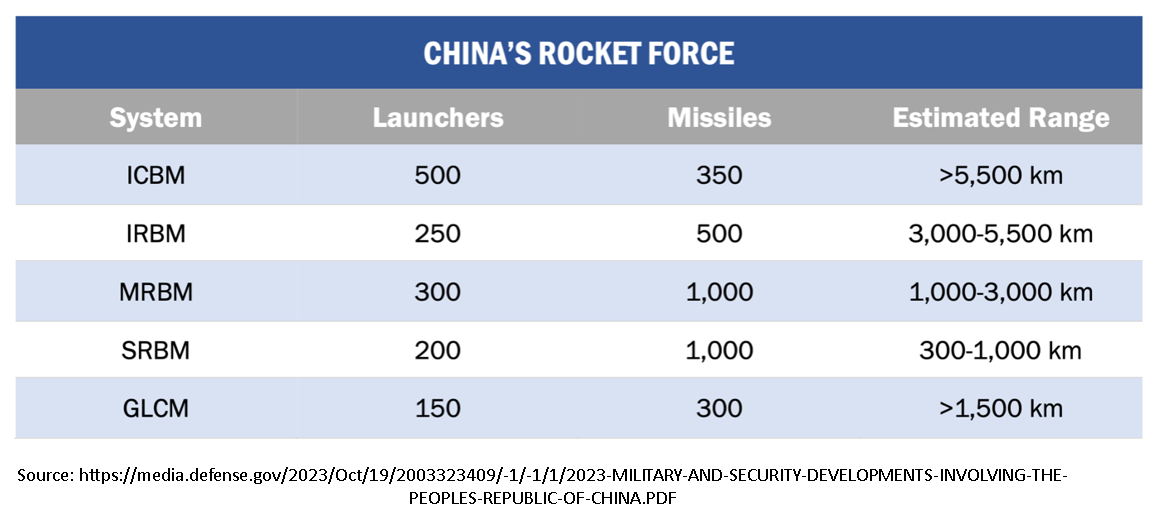

As per US estimates, PLARF has approximately 3,150 missiles of different varieties. The broad details are tabulated below. The conventional portion of PLARF could have about 2,500 ballistic and cruise missiles.

It is assessed that China has adequate anti-ship missiles to attack every US surface combatant vessel in the South China Sea after overcoming each ship’s missile defense. China’s nuclear arsenal is smaller than that of the United States or Russia. However, as per the latest reports, China has over 500 nuclear warheads and is on track to double these warheads to around 1,000 by 2030.

China’s nuclear arsenal is constantly upgrading, modernizing, and expanding. A notable feature of the expansion and modernization of the PLARF is that China has improved upon the accuracy of its missiles with much smaller CEPs.

The long-range precision strikes of PLARF can disrupt ISR, EW, AD, command and control, and logistics operations of its adversaries, besides hitting challenging targets. It is expected that the PLARF has integral ISR and AD and is fully integrated and equipped to fight “an informatized” battle, as per PLA doctrine.

Apart from posing strategic deterrence, the PLARF has presumably been equipped with adequate capabilities and capacities to suppress enemy air defenses and deny Chinese land, air, or sea space. The PLARF enables China to carry the battle into enemy territory.

The PLARF’s main focus areas are Taiwan and the South China Sea, but it also maintains capabilities against the Korean Peninsula, India, Russia, and the United States. China focuses on anti-ship ballistic missiles.

The DF-21 and DF-26 are projected as ‘carrier killers’ mainly to counter US carrier battle groups. China also intends to use PLARF to deny the USA access to the region via land, air, and sea and inhibit its ability to assist regional allies.

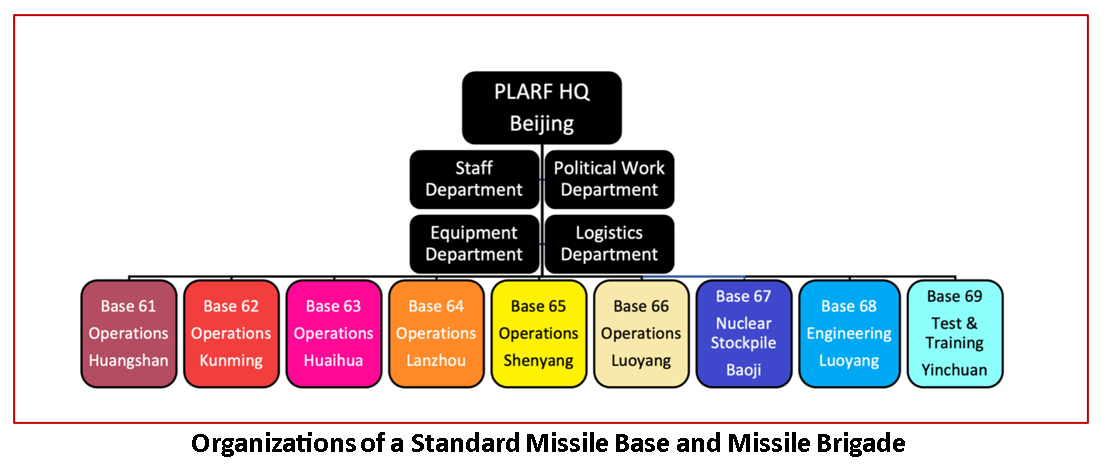

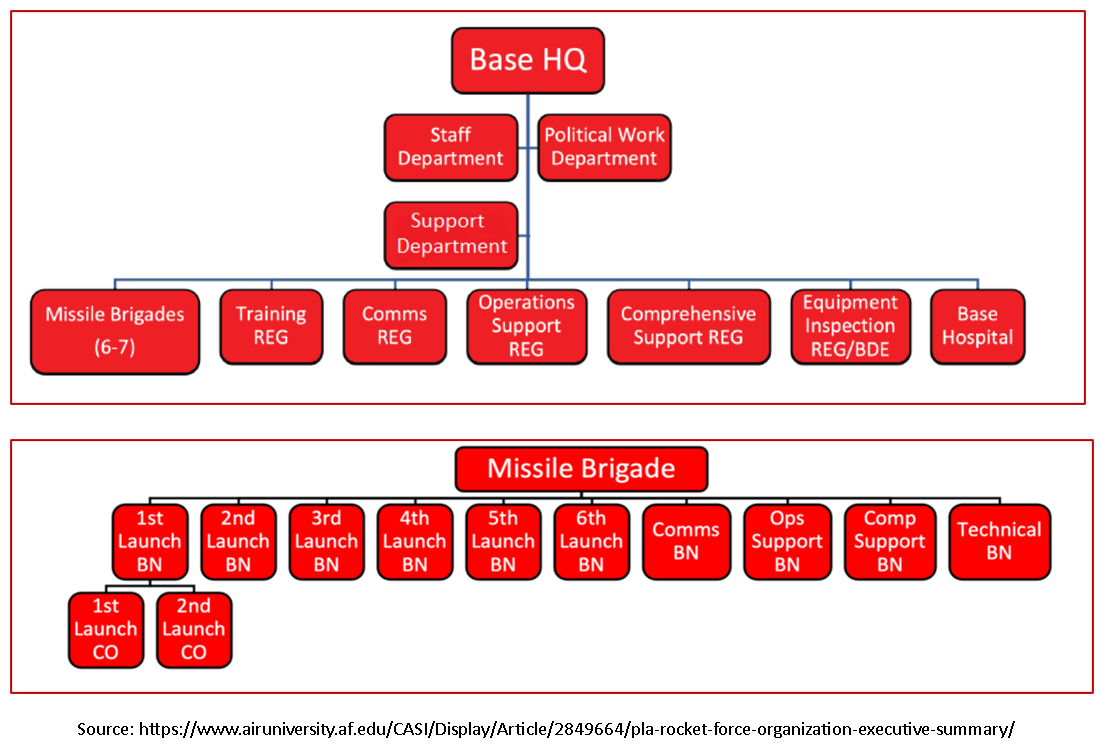

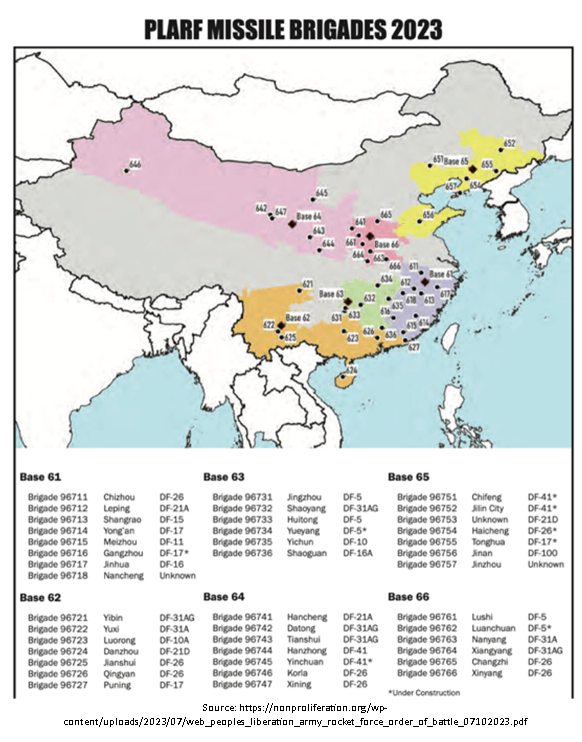

The PLARF currently has at least 40 combat missile brigades. These are organized into six “bases,” each of four to eight brigades. The missile bases are numbered 61-66. The standard organizations of missile bases and brigades are given above.

Each base corresponds to a geographic area in China, as shown in the map. Each brigade consists of several battalions or independent companies armed with a specific type of missile. These units could be either conventionally armed or nuclear-tipped.

Conventional missile brigades could have up to thirty-six launchers with six missiles each. Mobile nuclear missile brigades could have between six and twelve launchers. Deployment in silo-based nuclear missile brigades may vary since this scenario is under change.

The smaller the missile, the more launchers in a brigade. Missile brigades equipped with SRBMs (DF-11A or DF-15B) typically have up to 36 launchers per brigade. Medium and intermediate-range systems may have between 24 and 36 launchers.

China’s nuclear warheads are stockpiled in an additional base (Base 67). They are kept separately from the missiles. Interestingly, the size of support units at Base 67 has not increased in the recent past. It indicates that either a new base is coming up or there is a shift to stockpiling near new siloes (which are coming up). This aspect needs monitoring.

The PLARF has six SRBM brigades equipped with the DF-11, DF-15, and DF-16 systems. These systems enable the PLA to strike critical time-sensitive targets like command and control nodes, weapon stockpiles, and airbases in a regional conflict.

These systems are capable of carrying a variety of warheads specific to the target. The reach and coverage of each system from approximated launch positions are given below.

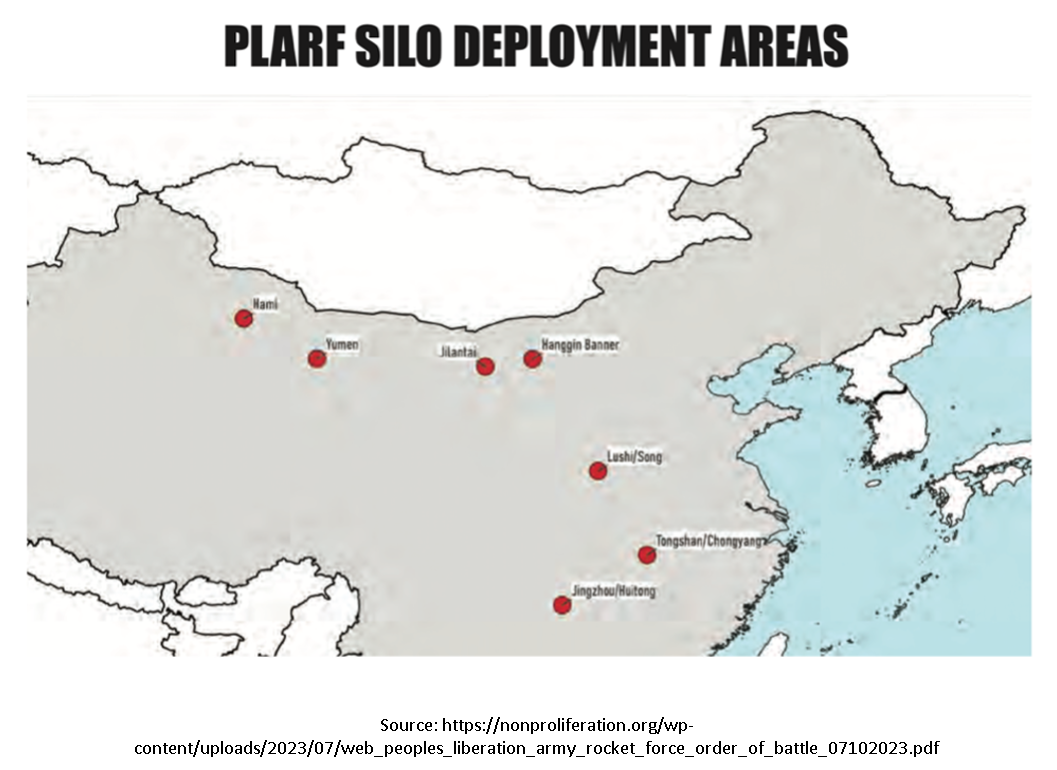

A noteworthy point is that China is expanding its silo-based deployment extensively. The massive expansion in silo-based deployment could be due to three reasons.

Firstly, the Chinese might feel that their mobile forces might not survive the first strike. Secondly, the large silos create a ‘missile sponge’ to absorb a first strike and still be capable of retaliating. Thirdly, it provides deception capability.

Silos being constructed are of two types: those holding solid propellant missiles and those having liquid-fueled ones. Rockets in the solid-fuelled silos are those which are part of their continuous alert standby system. It is also reported that additional storage facilities could be under construction near these silos. This gives China a ‘launch on warning’ capability.

It is further reported that China is constructing three new solid-propellant silo fields at Yumen, Hami, and Hanggin Banner, which could cumulatively hold at least 300 new ICBM silos. A large part of the construction was completed in 2022, and some of these silos could be loaded with ICBMs already.

The PLARF is also expanding its liquid-fuelled silos from where it can fire DF-5 missiles. Liquid-fuelled missiles like the DF-5 can carry much heavier payloads than solid-fuelled missiles. Hence, the number of warheads (especially the MIRVs) can increase manifold on such missiles.

Multiple warhead employment implies a slight increase in the number of missiles, which will have an out-of-proportion jump in China’s capability. The idea seems to be to increase these silos from the current 18 to at least 48 operational missile silos over the next three years. Some of these silos could have mixed ICBMs.

In addition, China is also expanding the number of mobile launchers. A point to be noticed is that all new siloes are coming up deep in China, away from the coasts. Apart from proving depth, this deployment also increases reach into the USA, Europe, and Russia.

Overall, the issue with China’s missile forces is not the numerical expansion in launchers or missiles. It is a shift from retaliatory deterrence to assured deterrence. It is also based on conveying a high degree of ambiguity in using conventional or nuclear warheads. Missiles with interchangeable warheads enhance this capability.

The missile development and deployment indicates a credible ability to defend itself or be offensive. It has enabled China to shift from a mere No First Use force to conveying a possible first use without implicit declaration. The new posture allows China to take the initiative to determine if the conflict remains conventional or otherwise.

Analysis

The rationale of the PLARF needs understanding. This force offsets China’s lack of overseas bases, aircraft carriers, and modern fighter aircraft to project power globally. It also neutralizes the inability of China to operate a vast overseas fleet globally, especially since it does not have enough people or experience to pilot its aircraft or captain its ships.

This is not what China wants, but this is what China has to do with. On the other hand, China’s missile inventory is traditional and the cheaper option for its power projection. It probably achieves China’s aim. Overall, this situation will not change for the foreseeable future. Trying to copycat/replicate the PLARF in India’s context needs a rethink. India must play to its strengths and requirements.

The PLARF assets will be high-value targets in any conflict scenario. However, all writings on the PLARF read so far lack detail on protecting these assets from the air. China’s missile interceptor systems are still under trial and depend on the S300 system it acquired from Russia. The absence of a layered air defense capability does indicate a vulnerability that can be exploited.

The PLARF is a formidable strategic force that can be used at operational depths. Its role in tactical scenarios is, however, limited. Once past the stage of the initial battle, its impact will diminish in any scenario.

Further, as the battle prolongs, the role and efficacy of rockets and missiles is also limited. A prolonged campaign will nullify the advantage PLARF confers on China. This has been very clearly seen in the Ukraine war and Israel-Hamas battles. Once the battle begins, the ability to fight and win at tactical levels is more critical. The PLARF will not win wars for China the way it is being painted and propagated.

China’s deployment of any missile/rocket system in Tibet is primarily to compensate for its lack of manned air capability in high altitudes. The PLARF does not confer a great advantage to China at the tactical and operational level along the Line of Actual Control with India. Also, the efficacy of these systems in high altitudes has yet to be proven.

There is no doubt that PLA enjoys a preponderance of missile and rocket power vis-a-vis India. However, the deployment of the bases and units of PLARF indicates a vast bias to its populated and economically critical eastern areas as against Tibet.

Very clearly, China cannot redeploy its entire arsenal against India and leave itself vulnerable in the Han heartland. Most current assessments are from Western sources who state the case from their perspective.

It is highly likely (I am sure of it) that we are over-assessing the threat from PLARF qualitatively and quantitatively in a conventional scenario. A realistic assessment is therefore needed in a China–India context by our think tanks/Services. The nuclear equations are different with different dynamics and not being discussed further.

In the harsh Tibetan terrain, the ability to deploy these heavy rocket and missile systems is limited by many factors. These factors enable neutralizing the strengths of the PLARF. Controlling the ingress/egress routes and deployment areas of PLARF assets will pay handsome dividends in the Himalayas.

Commanders should use intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities to identify PLARF assets and use either special operations forces or long-range precision fires, either integral or air support, to neutralize the threat these missile systems pose. ISR can also identify if a PLARF unit is a conventional or nuclear unit to permit the commander to react accordingly.

India should not compete with China quantitatively. We must look at the outcomes we desire on a minimal-cost basis. India should instead focus on qualitative offsets. The qualitative offsets come from imaginative deployment by exploiting terrain, incorporating a layered air/missile defense, selective hardening of own assets, layered air defense, and deception to fool the Chinese into striking false targets.

A philosophy of deterrence by denial will yield immense benefits. It will degrade the danger of overwhelming long-range precision fires. However, it needs diligent and painstaking joint planning.

Last but not least, the PLARF is generously funded by China. Hence, a lot of corruption is involved. This is clear from the recent sacking of their Defense Minister and the top leadership of PLARF.

The Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission has also publicly mentioned the substandard quality of items. The larger picture of PLARF, which emerges, is that of a well-funded force with corrupt leadership and substandard equipment.

It is to be seen if this status is permanent or an aberration. One will never know since the bulk of this force will not be used in any battle!

- Lt Gen PR Shankar is a retired Director General of Artillery of the Indian Army. He is now a Professor in the Aerospace Department of the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras. He can be reached at pravishankar3 (at) gmail.com. VIEWS PERSONAL

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News