The first-ever collaboration on space technology between India and China may now be in the doldrums as a key scientific instrument produced in India for China’s Tiangong Space Station is struggling to secure export clearance.

An application for an export license for the Spectroscopic Investigations of Nebular Gas (SING) equipment was submitted by a team from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics in Bangalore last year. However, Indian scientists now contend that they have hit a roadblock while pushing for its export clearance, SCMP noted.

Almost a year after the decision was made to supply the equipment to China, the team says it has not learned of any new progress on the application. The project manager and astrophysicist Jayant Murthy told the media, “We completed everything two months ago. The instrument is now in the clean room, ready to fly.”

Although the inability to secure export clearance is worrying, it may not entirely be surprising to Indian scientists. The scientists had previously expressed concern that the Sino-Indian tensions that started with a border standoff in eastern Ladakh could cast a shadow on the export of the equipment.

Murthy earlier told the media, “We are cautiously hopeful that the project will progress as scheduled. Technical discussions on the payload are still on with China, and we have conveyed to them that we need an export clearance from Indian authorities to proceed. We have written to our relevant agencies and are awaiting their response.”

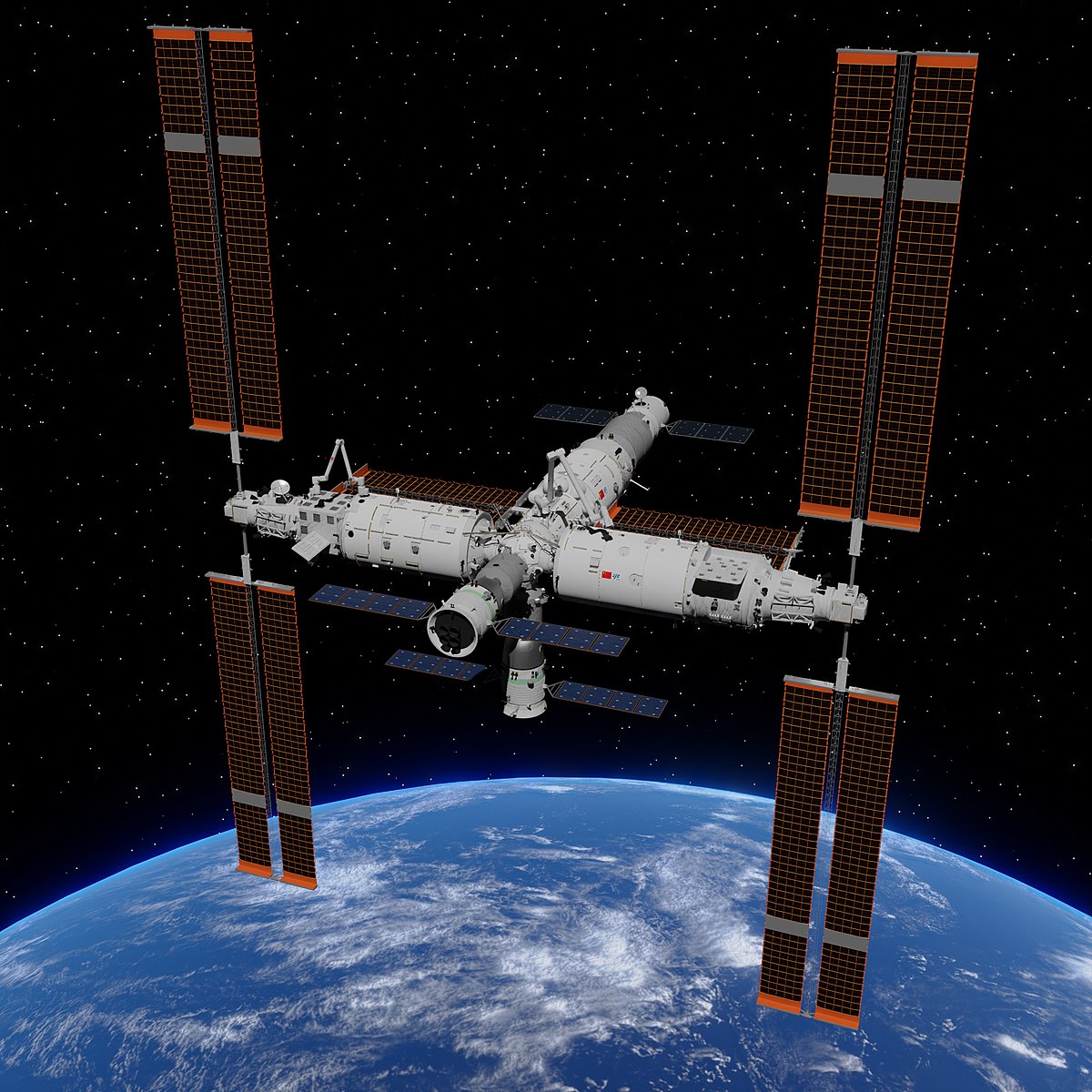

SING was jointly chosen as one of nine international experiments on board Tiangong by the China Manned Space Agency and the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs.

In 2019, nine groups from 42 applications, including scientists from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA), Bengaluru, were chosen by a UN-led initiative that encouraged research teams from all over the world to compete for the opportunity to design payloads that will be shuttled to Tiangong.

The US$50,000 equipment, which is supposed to be put on Tiangong as part of the first India-China partnership in space science, is expected to scan the sky in the ultraviolet waveband as it orbits the Earth to assist researchers in better understanding the makeup and behavior of interstellar gas, the birth and death of stars, and other related phenomena.

In the past, India and China have worked together on research initiatives like the Giant Meter Wave Radio Telescope used by astronomers worldwide to study radiation at meter-scale resolutions to detect and analyze stars and galaxies. However, the SING project would be significant as Tiangong takes shape.

With the global community coming forward, the lack of export clearance for India’s SING is being viewed as a setback for India’s scientific community. If the SING makes it to China this year, it would perhaps be the first-ever international payload to operate on the Chinese space station.

Murthy told the media that even though the majority of SING’s components, such as a telescope and spectrograph, were created by him and his graduate students, the hostile relations between India and China did not help. “I’ve tried to explain that our instrument would be pointing up towards the sky and not looking down at the Earth at all, but that did not work,” he said.

When asked whether the delays in export could be attributed to the Sino-Indian tensions along the border, space, and defense expert, Omkar Nikam told EurAsian Times: “The current situation between India and China has definitely affected several segments, but consumer market and scientific cooperation still thrives. Though there are several complications, it is to be noted that encouraging such collaboration between two states with little or no common interests is something that will strengthen diplomatic ties and keep up healthy cooperation in critical sectors like space.

Although India and China regularly hold border talks, there has been little breakthrough, with New Delhi insisting that the PLA return to pre-2020 positions. While China continues to call for normalization in ties, Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar has consistently iterated that it was not an acceptable position.

Group Captain Arvind Pandey (Retd), a geospatial intelligence professional, told EurAsian Times: “The contract was bagged in a contest that is being overseen by the United Nations Outer Space Office and is not a bilateral thing between India and China, so it is unlikely that India will hold back the equipment. And it is being built in collaboration with the Russian Academy of Sciences. These reports generate in Chinese media to create a narrative that India is holding back crucial supplies. The equipment is bound to be cleared for export sooner or later.”

When the International Space Station (ISS), led by the United States, deorbits at the end of this decade, the Chinese Tiangong will be the only space station in the world. Researchers worldwide are now conducting experiments aboard the Tiangong in what is Beijing’s appeal to the global scientific community.

While the export delays may not be due to the bilateral tensions between the countries, it does, incidentally, come when India advances its space cooperation with the United States.

India-US Space Cooperation Is Taking Shape

The White House announced a significant development in bilateral space collaboration on June 22, while Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was in Washington, DC, for a meeting with American President Joe Biden. India became the 27th country to sign the US-led Artemis Accords.

The nations taking part in NASA’s Artemis program are governed by a set of practical principles laid forth in the Artemis Accords, establishing a framework for international collaboration on space exploration.

The agreement was a culmination of several attempts to advance space cooperation. For instance, a special US-India Space Technology Industry Workshop on Export Controls was held in April 2023, sponsored by the US Department of State’s Export Control and Border Security Group (EXBS) and the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS). This workshop was intended to “expand India’s commercial and defense cooperative engagement in the space sector.”

Welcome to the #Artemis Accords, India! 🇮🇳

By signing the Accords, India has become the 27th nation to commit to the safe and peaceful exploration of deep space: https://t.co/BjcD8gF6ko pic.twitter.com/5ZVzwagiIz

— NASA Artemis (@NASAArtemis) June 24, 2023

With the signing of the Artemis Accord, India would be allowed to participate in the US-led Artemis initiative for the moon and other celestial object investigations. The agreement will also open the door for lifting import restrictions on critical technologies for space, particularly electronics, which is expected to help Indian businesses create new products and systems for US markets.

Additionally, and more significantly for the Indian science community, it will make it easier for India to participate in more joint scientific initiatives, give access to common standards for long-term collaborations on projects like human spaceflight initiatives, and foster stronger ties with the US in more strategically essential fields like microelectronics, quantum, space security, etc.

The Indian Minister for Science and Technology, Dr. Jitendra Singh, said, “Though India and the US have been collaborating in the Space sector for a long time, the journey in the last nine years of the Modi Government has taken off on a growth trajectory. India is no longer lagging in Space exploration, and today, we are equal partners in Deep Space Missions,” he said. Dr. Jitendra Singh clarified there are virtually no restrictions and no technology denial by the US. “We are today technologically capable,” he said.

On his part, NASA chief Bill Nelson has accused China of not cooperating in space and ushering in a space race instead. Earlier, he said in a press conference at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida that “we want cooperation that has not been forthcoming from the Chinese government [but] it takes two to tango.”

However, China lamented that it was the Wolf Amendment, introduced in 2011, which practically forbids any direct cooperation between NASA and its Chinese counterparts.

This may have made India’s cooperation with NASA and joining Artemis Accords an even deeper wound for China. On its part, Beijing continues to accuse the US of trying to contain China’s influence by making a regional clique using regional powers like India.

Against that backdrop and without a smooth bilateral relationship between India and China, the export license hanging in the air could be a setback for both sides. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) has not commented on the development.

- Contact the author at sakshi.tiwari9555 (at) gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News