OP-ED By Ria Deval & Saba Sattar

The 2021 UN Climate Change Conference, better known as the COP26 summit, failed to include a key item on its agenda: military emissions. World leaders discussed, inter alia, an ambitious goal of achieving carbon neutrality by the year 2050.

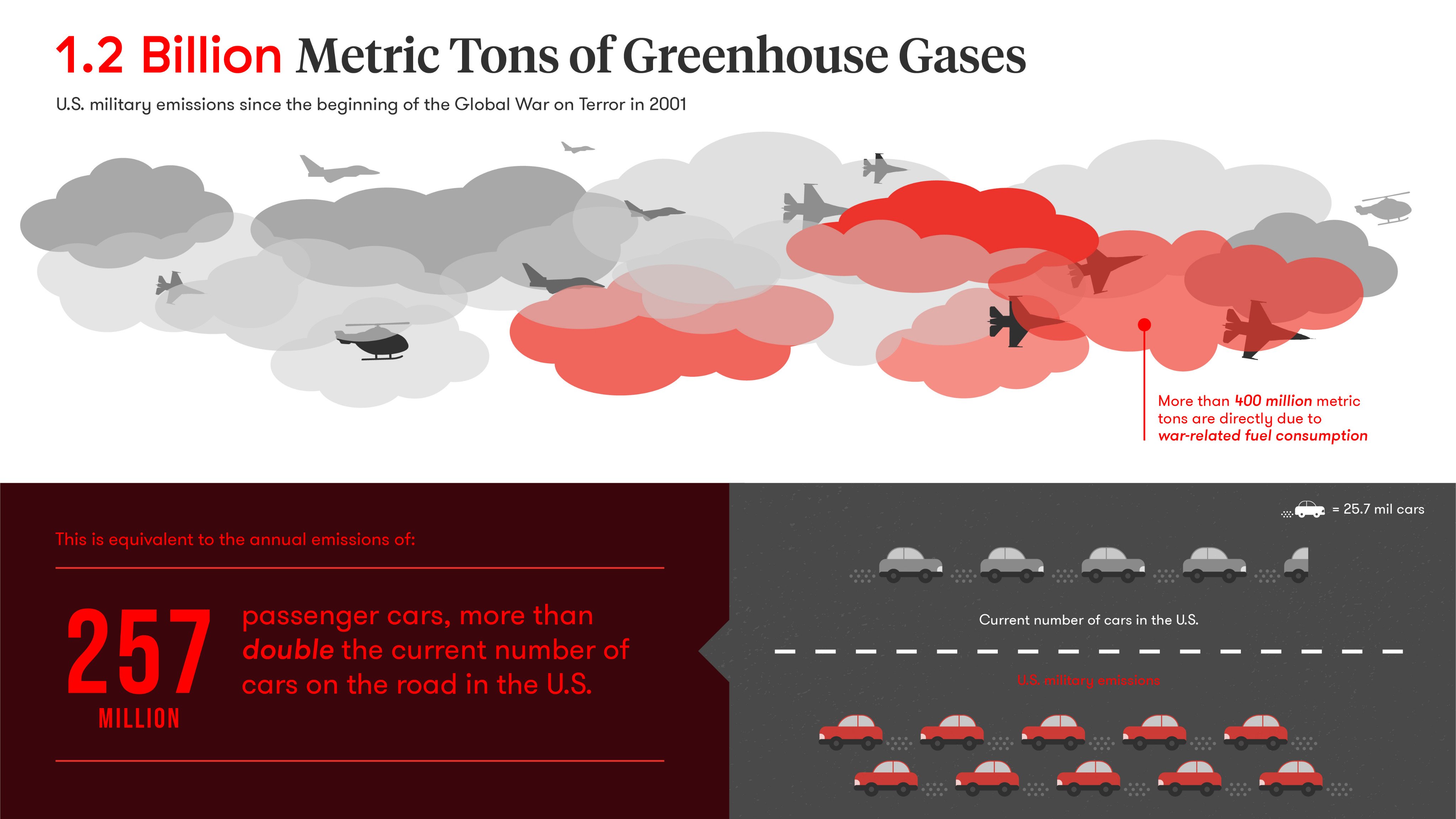

Despite the large role of the military, little data is disclosed regarding their emissions. Military emissions are consistently excluded from climate change agreements and summits. In 2015, the Paris Agreement — an international agreement with a whopping 192 signatories — left military greenhouse gas emissions to the discretion of individual nation-states.

Militaries are one of the last highly polluting industries whose emissions do not need to be reported to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which implements and oversees such agreements. The lack of mandatory reporting means that voluntary assessments generally remain incomplete and exclude statistics on transmissions generated from the development of advanced material and the usage of petroleum-based transportation, in addition to those related to the impact of conflict operations.

Defense equipment is not exactly renowned for its fuel efficiency. It is estimated that the US’ residual fleet retains a mere four to eight miles per gallon.

In 2020, global military expenditure rose by 2.6 percent to nearly $2 trillion. In 2017, the US armed forces emitted 59 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Other large military spenders, such as China, Russia, and India, are less transparent about their transmission levels as their economies are largely dependent on hydrocarbons.

Global Military Carbon Footprint

According to the Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR), the global military carbon footprint, including the defense supplying industries, contribute to an aggregate of 6 percent of all emissions. As civilian modes of transportation make a transition away from gasoline, military-grade vehicles may become the remaining few to stay carbon-dependent. Over the long haul, militaries around the world will need to phase out fossil fuels in a sustainable manner — an objective that must not be rushed or become politicized.

In April, US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin declared global warming as an existential threat to US national security during a White House climate summit. Using language normally applied to conventional adversaries, such as China and Russia, Gen. Austin described the climate crisis as “a profoundly destabilizing force for our world.”

He further asserted, “When we operate more sustainably, we become more logistically agile and ready to respond to crises… None of us can tackle this problem alone. We share this planet, and shared threats demand shared solutions. I look forward to working with all of you on this vital mission.”

In June, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) summit addressed climate change by pledging a goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 — echoing what world leaders discussed at COP26 but specifically tailored towards defense-related programs and activities.

While NATO member states have brought the climate change agenda to the fore, Gen. Austin’s remarks on championing shared solutions will need to incorporate nations beyond the developed world. At the center of this debate is India: the world’s largest democracy that put forth a stumbling international block during the COP26 summit.

Focus On India

Since the Biden administration prioritizes its climate change agenda, there are new opportunities for cooperation between India and the US both bilaterally and through the QUAD (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) framework. India seeks to enact reforms within its own military.

Across the country, the Indian military is taking some steps to improve sustainability and efficiency. In 2017, the Joint Doctrine of the Indian Armed Forces outlined climate change and environmental disasters as nontraditional security threats. In 2019, the Indian Army removed 130 tonnes of solid waste from Siachen Glacier to protect its ecosystem. Among other initiatives, this year, the Indian Army inaugurated the First Green Solar Energy harnessing plant of 56 KVA in North Sikkim, in order to harness renewable energy for its troops.

At the bilateral level, the US and India should hold meetings and implement action plans tailored to their domestic militaries. At the UN climate conference (COP15) in 2009, developed countries pledged to mobilize $100 billion per year by 2020 to support developing countries to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

This commitment was reaffirmed in the Paris Agreement adopted at COP21 in 2015, where countries agreed to set a new collective goal to provide $100 billion every year to 2025. While final figures will not be fully released until 2022, it is generally accepted the 2020 goal has not been fully met. COP26 restated the importance of achieving this goal, highlighting climate finance as one of the four main goals of the conference.

If this goal is met, Biden can allocate some of this money to transform the military sector in developing countries with green measures. By taking the first steps in transforming India’s carbon-intensive economy to one of clean energy, the US will be able to guide high-emitting countries down a more sustainable path.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, India has already taken a hit with its defense preparedness; Biden will need to exercise patience while setting realistic benchmarks to accomplish these essential objectives.

Since Biden was inaugurated, climate change has been prioritized during the QUAD summits. To enhance India’s participation in the quadrilateral mechanism, the US should encourage the world’s largest democracy in leading the conversation on climate change.

World today admits that lifestyle has a major role in climate change. I propose one word movement before all of you. This word is LIFE which means Lifestyle for Environment. Today, it's needed that all of us come together & take forward LIFE as a movement: PM Modi at #COP26 pic.twitter.com/nXoBV8StUy

— ANI (@ANI) November 1, 2021

During the COP26 summit, Modi took a stand for the developing world by arguing in favor of sustainably phasing out the use of fossil fuels. Western states, such as the US, need to recognize that many states in the developing world are newly independent of the colonial period and should not rush the transition to renewable energy sources in an unfeasible manner.

The Biden administration can collaborate with India both at the bilateral and multilateral levels to prioritize climate change. The COP26 summit failed to address military emissions — a large obstacle that stands in the way of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. The QUAD summit provides an existing framework to tackle military emissions in some of the world’s most carbon-intensive economies. The US and India can lead the conversation in mitigating this longstanding national security threat.

- Ria Deval is a student of International Affairs at George Washington University. She is a current intern at the Foundation for Food & Agriculture in Washington, D.C. and a former research assistant of the Near East South Asia (NESA) Center for Strategic Studies, a regional center for the United States Department of Defense.

- Saba Sattar is a doctoral candidate of Statecraft and National Security at the Institute of World Politics in Washington D.C. She specializes in U.S.-India security relations across the conflict continuum, from addressing the low-intensity conflict in Kashmir to Chinese revisionism in the Indo-Pacific. She holds an M.A. in Statecraft and National Security Affairs.