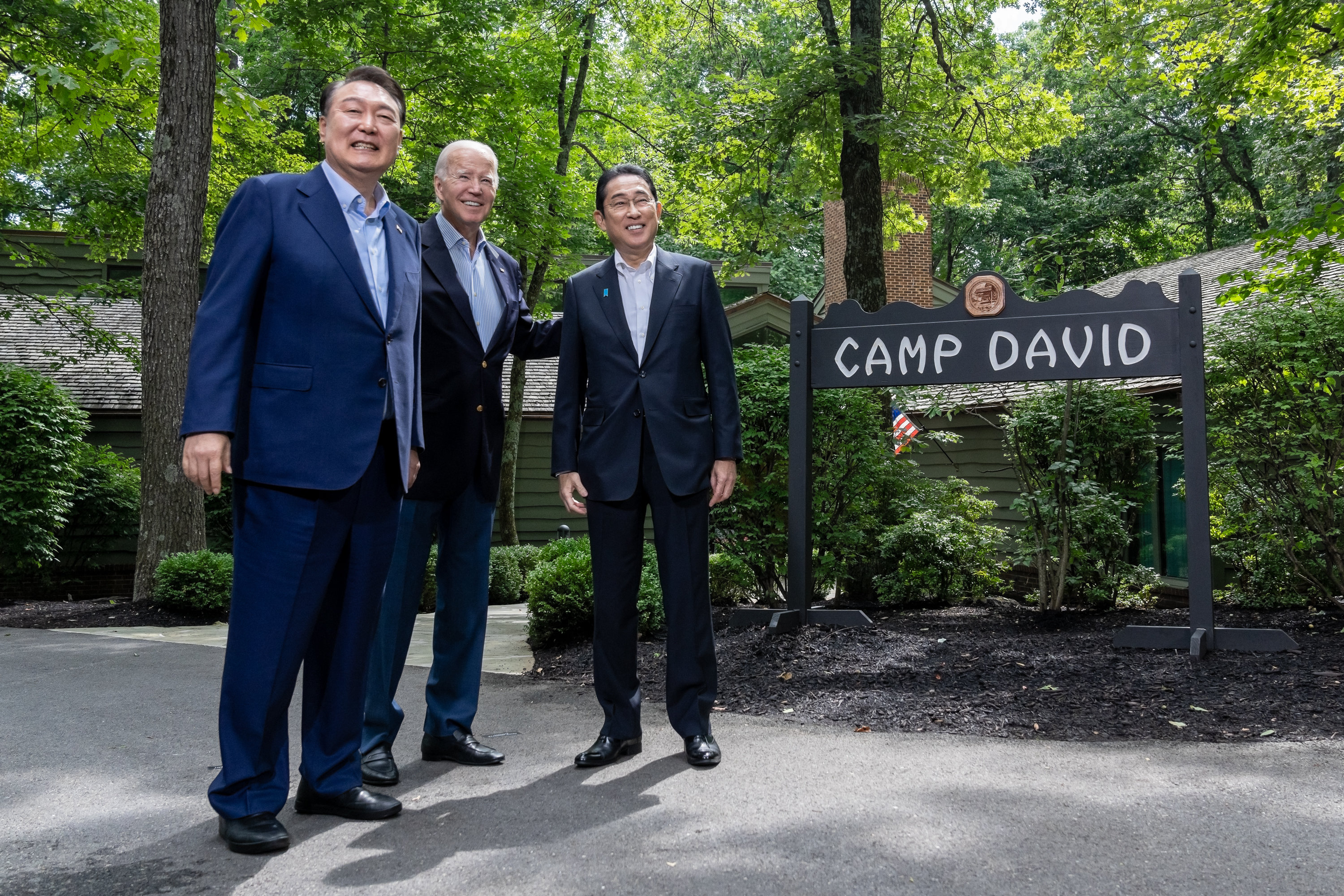

At first glance, the first standalone summit among US President Joe Biden, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol at Camp David on August 18, again the first time that the Biden Administration has used the venue for an international meet, reflects a broader approach to the building of rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific.

On closer scrutiny, however, questions arise as to whether the spirit that the three leaders displayed at the summit would be sustained in the days to come, given the bitter history involving Japan and South Korea on the one hand and the critical China factor on the other.

Let us first see what they agreed on.

“As Indo-Pacific nations, Japan, the Republic of Korea (ROK), and the United States will continue to advance a free and open Indo-Pacific based on a respect for international law, shared norms, and common values. We strongly oppose any unilateral attempts to change the status quo by force or coercion”, a statement titled “Camp David Principles” issued at the end of the summit emphasized.

Through their lengthy joint statement, titled “The Spirit of Camp David,” the three leaders pledged to promote and enhance peace and stability throughout the Indo-Pacific while expressing worries over the future of the Taiwan Strait and North Korea’s nuclearization and missile threats.

They talked of economic cooperation by developing “the Partnership for Resilient and Inclusive Supply-chain Enhancement (RISE)” to help developing countries play larger roles in the supply chains of clean energy products.

They agreed on expanding trilateral collaborative research and development and personnel exchanges, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) sectors, open radio access network (RAN), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and space domain.

There was another statement on “Commitment to Consult,” in which they said, “We, the leaders of Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the United States, commit our governments to consult trilaterally with each other, in an expeditious manner, to coordinate our responses to regional challenges, provocations, and threats affecting our collective interests and security. Through these consultations, we intend to share information, align our messaging, and coordinate response actions.”

Rarely does a summit bring out as many as three statements by the participants. But that is what the latest Camp David summit has witnessed.

Be that what it may, the summit dispelled ideas visualized in many quarters that the trilateral agreement at the Camp David summit would imply an Asian NATO. The transatlantic military alliance, in Article 5, talks of commitment to mutual defense (an attack on one is an attack on all). But the summit only talked of “commitment to consult.”

It said, “Our countries retain the freedom to take all appropriate actions to uphold our security interests or sovereignty. This commitment does not supersede or otherwise infringe on the commitments arising from the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between Japan and the United States and the Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and the Republic of Korea. This commitment is not intended to give rise to rights or obligations under international or domestic law.”

Thus, it can be said that the “commitment to consult” outlined at Camp David is closer, at best, to Article 4 of NATO, under which member nations can bring any security issue to the table for discussion.

In a way, as pointed out in the “commitment to consult,” both South Korea and Japan have their respective treaties with the US. If these two treaties are seen together, the US, Japan, and South Korea possess formidable defense capabilities and host around 100 permanent US military bases and approximately 80,000 US troops in the region.

What is new here following the summit is that Japan and South Korea will come together in the future to chalk out a shared strategy in the event of any major security concern.

Japan and South Korea do not have a formal security alliance. The two have had serious domestic hurdles dating back to the days of Japanese colonization of Korea (1910-45) for any structured alliance. In Korean politics, Korea’s demand for periodic atonement for the excesses it committed and compensation to the affected Korean families have been a hot issue. Besides, there are territorial disputes over some islands between the two.

It may be noted that many attempts in the past by the United States to bring Japan and South Korea together to develop a shared security outlook have not exactly worked.

For example, when in 1998, North Korea launched its first multistage ballistic missile over Japan, the then South Korean President Kim Dae-jung and Japanese Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi held a historic meeting in Tokyo, where the latter offered an official apology for Japan’s colonial occupation of Korea.

This helped in creating “the Trilateral Coordination Oversight Group” in 1999 among the US, Japan, and South Korea. But it could not be sustained as the Korean and Japanese leaders succumbed to domestic pressure and revised the historical animosities.

The situation further worsened when in 2012, South Korean President Lee Myung-bak made a controversial visit to a set of islands—known as Dokdo in South Korea and Takeshima in Japan—that both South Korea and Japan claim as their own and in 2013, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited a shrine that honors Japan’s war dead, including convicted war criminals, angering South Korea.

Years under Yoon’s immediate predecessor, President Moon Jae-in, further nurtured anti-Japanese feelings. Moon scrapped the foundation that Tokyo and Seoul had set up with Japanese funding to provide restitution to the victims and their families.

In 2018, South Korea’s Supreme Court ordered several Japanese companies to compensate unpaid South Korean World War II laborers. This prompted a series of new punitive measures from each side, driving relations to a nadir in 2019. Japan imposed sanctions on the Korean semiconductor industry.

However, what Biden, Kishida, and Yoon have done over the last year is that they have sincerely and actively tried to rise above these historical animosities and join hands together in the face of mounting North Korean aggressiveness and the Chinese hegemony, something all three consider to be their common threats.

Yoon has often pointed out that “South Korea and Japan are now new partners who share universal values and pursue common interests.” He has emphasized the importance of Japan in South Korea’s security, particularly the seven rear bases provided to the United Nations Command by Japan, which could “serve as the greatest deterrent” to North Korea invading the South.

Under Yoon, South Korea has restored and expanded joint military drills (suspended under Moon to what was said “appease” China; he was believed to be the most pro-China President in South Korean history) and joined exercises with the US and Japan to track and intercept missiles from North Korea.

Yoon proposed an initiative in March to resolve disputes stemming from compensation for wartime Korean forced laborers. He announced that South Korea would use its own funds to compensate Koreans enslaved by Japanese companies before the end of World War II.

And on his part, Kishida has rolled back the sanctions on South Korea. He has also held off on releasing the treated radioactive water from the destroyed Fukushima nuclear power plant, another contentious issue in South Korean politics.

Yoon also traveled to Tokyo in March for talks with Kishida, the first such visit by a South Korean president in over 12 years. Kishida reciprocated with a visit to Seoul in May and expressed sympathy for the suffering of Korean forced laborers during Japan’s colonial rule.

Against this background, the Camp David summit is significant as it was the first standalone meeting of the heads of the US, Japanese, and South Korean governments dedicated to trilateral cooperation.

But despite the rapid progress made over the past year, the future success of this trilateral cooperation is not assured, say many experts. There seem to be two essential factors.

One is the importance of China for economic reasons for both Japan and South Korea. China has criticized the trilateral cooperation seriously, saying, “Attempts to cobble together various exclusionary groupings and bring bloc confrontation and military blocs into the Asia-Pacific are not going to get support and will only be met with vigilance and opposition from regional countries.”

While Japan is more willing than South Korea to tighten its export controls to align with US restrictions on Chinese industry, the fact remains that many in Japan fear that bolstering trilateral security cooperation will lead the country into an economic Cold War with China, its biggest trading partner.

Given its geographic proximity and relatively larger economic stakes in its relations with Beijing, Seoul is even more restrained in antagonizing China beyond a point. After all, South Korea exports more than 40 percent of its semiconductors to China. Korean firms such as Samsung have large production facilities in China.

Second is the factor of public opinion in all three countries in the near future. There is no guarantee that the succeeding regimes (if at all) will retain the same spirit displayed at Camp David on Friday.

The US is going for an election next year. If the regime changes, one may be reminded of the Trump years when the then US President was cultivating the North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un. Similarly, Kishida is now facing stagnant approval ratings at home, leading to speculations that he may call for sudden general elections.

Of course, Yoon himself does not face any elections for the next few years to be confronted by a challenger, but next April, South Korea will have general elections to the National Assembly, where a majority of legislative support is important for the South Korean President.

And here, the current opinion polls show that nearly 60 percent of South Koreans oppose Yoon’s handling of the forced labor issue central to mending relations with Japan.

Keeping all this in mind, Duyeon Kim, an adjunct senior fellow at the Seoul-based Center for a New American Security’s Indo-Pacific Security Program, says, “If an ultra-leftist South Korean president and an ultra-right wing Japanese leader are elected in their next cycles, or even if Trump or someone like him wins in the US, then any one of them could derail all the meaningful, hard work Biden, Yoon and Kishida are putting in right now.”

She seems to have a valid point.

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda is Chairman of the Editorial Board – EurAsian Times and has been commenting on politics, foreign policy, on strategic affairs for nearly three decades. A former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship, he is also a Distinguished Fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News