OPED By Amb Gurjit Singh

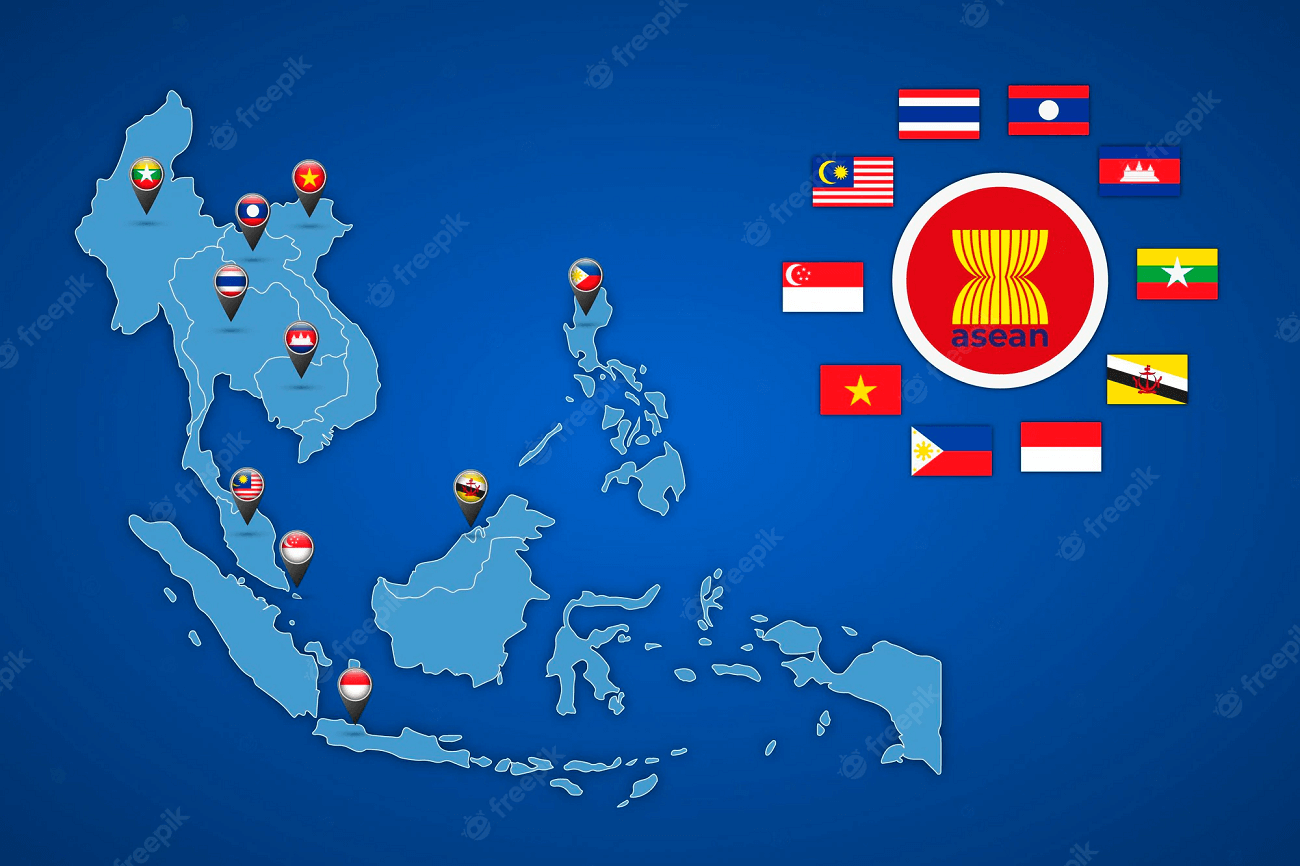

There is growing interest in ASEAN as a market for defense exports. While the ASEAN market has grown over the years, interest in it has increased because of the emergence of new partners for defense exports to the region.

According to SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, 2023 March edition, Southeast Asia’s military expenditure has grown from about $20.3 billion in 2000 to $43.2 billion in 2021.

Between 2002-2007, Southeast Asia military expenditure was less than $30 billion per annum, but it breached the $30 billion mark from 2008 to 2014; from 2015, Southeast Asian countries spent about $41 billion or more, with the peak being in 2020 at $44.3 billion.

It is significant to note that increases started around 2013, when expenditures jumped from $34 billion to $38 billion, and have been growing since. Since 2012 aggressive Chinese intent on the South China Sea has grown, splitting ASEAN but also bringing Chinese vessels to the waters and islands of at least five ASEAN countries.

It is pertinent to note that while for economic purposes, ASEAN countries have fully engaged China, when it comes to Chinese weaponry, the Armed Forces of most ASEAN countries have been reluctant and have actually expanded their engagement with traditional exporters and now towards emerging exporters.

This is also because there is hardly any military production within ASEAN itself. In the SIPRI List of 100 top military-producing companies, there are eight Chinese companies and four each from Japan and the Republic of Korea. The Singapore company S.T. engineering is the only one among ASEAN countries in the top 100 list.

In this context, the openness of ASEAN to buy cost-effective defense products from emerging countries is of significance. Indonesia is likely to conclude its $200 million deal to buy the naval version of BrahMos.

Earlier, the Philippines had surprised others by signing a $375 million deal with India for a shore-based anti-ship BrahMos version in 2021. This deal is currently under implementation.

These exports of BrahMos have been among the first through the most likely candidate, but Vietnam has still remained muted. India expects that BrahMos exports globally could attain the figure of $3 billion by 2026, which could perhaps help to meet India’s defense export target of $5 billion by the same time.

Similarly, South Korea has been enhancing its exports to ASEAN countries. In the most recent case, Korean Aerospace Industries, in February 2023, signed a $910 million contract to provide 18 F A 50 fighters to Malaysia; they overcame the competition of India’s Tejas aircraft.

While Malaysia is not among the big arms spenders within ASEAN, its engagement with South Korea and Turkey is growing. According to SIPRI, between 2017 and 2021, South Korea sold nearly $2 billion of defense equipment to Malaysia.

In fact, in this period, from 2017 to 2021, South Korea made ASEAN its dominant area for arms exports, followed by Turkey and the U.K. This experience in ASEAN is also helping South Korea expand to the East European countries.

In the case of Malaysia, the domination by France, Germany, and Russia between 2002 and 2011 has given way, and between 2017 and 2021, Turkey and South Korea are the major suppliers.

Researchers believe South Korea’s military equipment is priced attractively, which fits the budgets of ASEAN countries better than European or American suppliers.

South Korea has the advantage of obtaining technical transfers to build their industry in the past. Major ASEAN importers like Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia are looking at various sources to use their limited budgets.

The Philippines has become the leading buyer of South Korean weapons in the last five years, followed by Indonesia and Thailand. Vietnam, Myanmar, and Malaysia are also players in the South Korea-ASEAN defense engagement.

Where southeast where ASEAN countries are concerned, according to SIPRI, Singapore has the largest budget for defense from 2002 to 2021. In 2021, they had an expenditure of $11115 million.

The next largest was Indonesia which has an expenditure of $8295 million, which marginally decreased from the level of $ 9387 million in 2020. Since 2012, Indonesia has shown a leap in its defense expenditure from a level of $6531 to $8384 in 2013 and maintained a steady

level.

Thailand is the next major importer of weaponry with an expenditure of $6604 though it had a level of $ 7000 per annum for the previous three years.

Malaysia and the Philippines have both crossed the threshold of $3000 per annum and maintained it for about a decade. These are perhaps set to rise.

SIPRI does not have reliable defense expenditure figures for Vietnam but places them at around $ 5500 million annually. Vietnam ceased declaring its defense budget in 2018 when it was estimated at 2.36% of its GDP.

In December 2022, Vietnam held its first Def Expo. One hundred seventy exhibitors from 30 countries participated in a sign that Vietnam facing Chinese hostility consistently, is seeking to diversify its Russian defense base.

JSC Rosoboronexport of Russia, Lockheed Martin of the U.S., Airbus of Europe, BrahMos Aerospace of India, and Mitsubishi Electric of Japan participated in this diversified opportunity. Chinee companies, though invited, were absent.

Vietnam relied on Russia for about 70% of its imported weapons, and most of its large equipment was made in Russia. The dependence decreased to less than 60% in 2021.

The U.S. and South Korea appeared as significant suppliers in 2017, a year after the USA lifted an embargo on weapon transfers to Vietnam. ASEAN is uncomfortable with big power rivalry and created a set of ASEAN-centric institutions like the EAS and the ARF.

However, a big power rivalry directly between the U.S. and China has spilled onto their beaches. Strategically, ASEAN is uncomfortable with this and the emergence of the Quad and AUKUS in their region.

Individual ASEAN countries, particularly those threatened by China directly, believe that their strategic autonomy needs to be buttressed by more efforts to improve their defense capabilities.

Due to this, ASEAN defense budgets are slowly increasing. In order to keep away from the US-China rivalry and the problem with Russia, particularly after the Ukraine crisis, ASEAN countries would like to use their limited budgets for bigger bangs and therefore look to

emerging suppliers like South Korea, Turkey, and India, among others.

This is an opportunity that must be purposefully grasped by a groomed decision to push Indian defense exports, which have a competitive advantage in selecting ASEAN countries from India.

- Gurjit Singh is a former Ambassador to Germany, Indonesia, Ethiopia, ASEAN, and the African Union Chair, CII Task Force on Trilateral Cooperation in Africa, Professor, IIT Indore.

- Contact EurAsian Times at etdesk@eurasiantimes.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News