Murders and poisonings of Russian defectors are nothing new. They have been happening since 1937.

The international community is abuzz with the news of the alleged murder of Maxim Kuzminov, a Russian pilot who made headlines in 2023 by defecting to Ukraine in a daring helicopter flight across the border.

Kuzminov’s death in Spain has ignited speculation about the involvement of Russia’s foreign intelligence service and has once again brought into focus Moscow’s relentless pursuit of individuals labeled as traitors, regardless of where they might have taken refuge.

Reports emerging from Spanish media indicate that Kuzminov was shot dead in the southern town of Villajoyosa last week. The pilot had relocated there after he got Ukrainian citizenship in recognition of his defection.

While Ukrainian authorities have confirmed Kuzminov’s death, they have refrained from divulging further details, heightening suspicions surrounding the circumstances of his demise. Moscow, on the other hand, has neither confirmed nor denied any involvement in Kuzminov’s death.

Russian Spy Chief Speaks

However, on February 20, Russia’s spy chief was quoted saying, “This traitor [Maxim Kuzminov] and criminal became a moral corpse at the very moment when he planned his dirty and terrible crime.”

Previous reports from Russian state television suggested that Russia’s GRU intelligence agency had been instructed to eliminate Kuzminov, indicating a concerted effort to target the defector.

These reports, coupled with claims from Russian intelligence agencies indicating an active pursuit of the “traitor,” underscore Moscow’s unforgiving stance towards those it brands as traitors.

This resonates with the stance of Russian President Vladimir Putin, as articulated in an interview with the Financial Times on June 27, 2019, where he firmly declared, “As a matter of fact, treason is the gravest crime possible, and traitors must be punished.”

The latest incident has sparked renewed interest in the stories of Soviet or Russian defectors and adversaries meeting their demise abroad, frequently enveloped in layers of intrigue and uncertainty.

The tactic of executing—or, in some instances, attempting — bold acts of murder, then following them with a series of equally bold denials, reminds one of the erstwhile Soviet states.

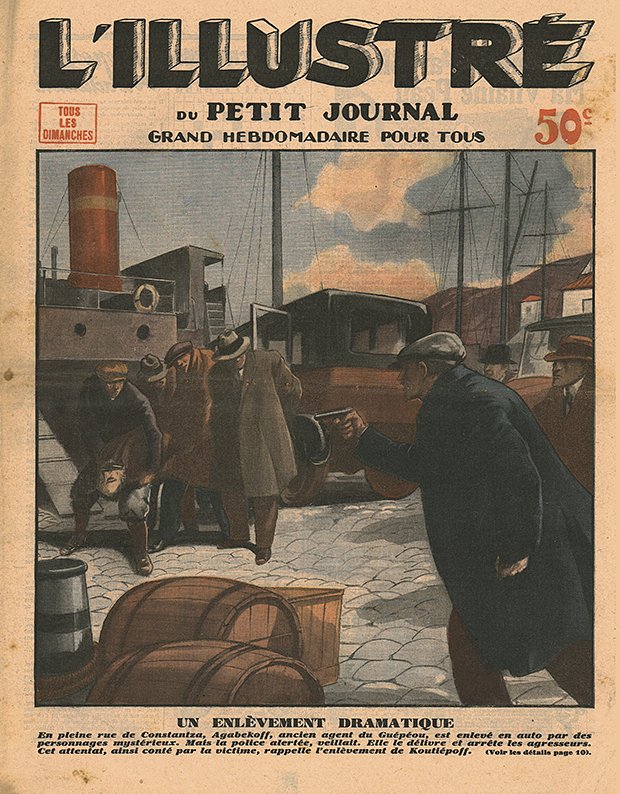

First Senior Soviet Intelligence Officer To Defect To The West

In August 1937, a specialized unit of the NKVD (Soviet secret police under Joseph Stalin) executed Georgy Agabekov in France, marking the beginning of a series of high-ranking defections from the ranks of Soviet foreign intelligence.

Often hailed as the first senior OGPU officer to defect to the West, Agabekov had fled as early as 1930, leveraging his position as a resident of the illicit intelligence service in Istanbul.

Upon relocating to France, he cited his departure as a response to his disagreement with the methods employed by Soviet secret services and Stalin’s overarching policies.

Several historical accounts assert that Agabekov’s decision may have been influenced by the execution of Yakov Blumkin, his predecessor as a resident in Istanbul, who was accused of ties to Trotskyites and subsequently sentenced to death.

Agabekov’s defection was further linked to his close relationship with Blumkin, who was suspected of sympathizing with Trotsky’s ideology. Additionally, his romantic involvement with Isabel Streeter, the daughter of a British intelligence officer in Istanbul, may have played a role in his choice to defect.

Despite his initial struggle to gain acceptance from Western intelligence services, Agabekov sought to prove his loyalty by publishing books detailing Soviet intelligence networks worldwide.

These revelations not only destabilized Soviet positions in countries like Iran but also compromised numerous undercover agents. While his publications brought Agabekov fame and fortune, they also dealt a severe blow to Soviet intelligence and diplomatic efforts globally, prompting Moscow to issue a death sentence against him.

In response, Russian intelligence agencies, led by Soviet colonel Alexander Korotkov, devised a plot to lure Agabekov to a secret meeting in Paris under the pretense of a deal involving stolen gemstones from Spain.

Agabekov fell for the ruse and traveled to the Pyrenees Mountains for the rendezvous near the Spanish-French border. There, he was met by a former Turkish army officer recruited by Soviet intelligence, who fatally stabbed him with a knife.

Mysterious ‘Suicide’ Of Soviet Military Intelligence Spymaster

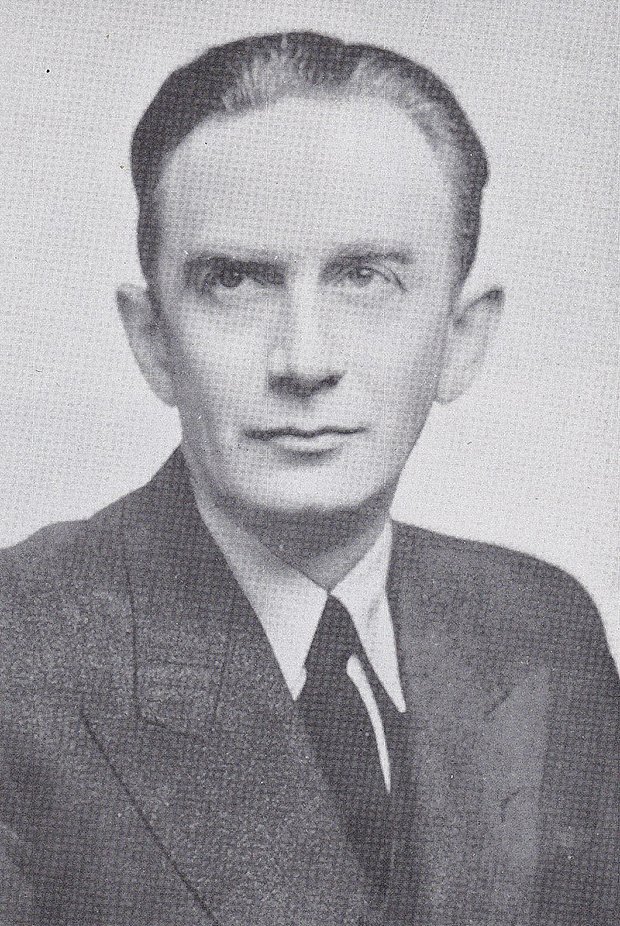

Walter Germanovich Krivitsky, also known as a Soviet military intelligence spymaster, gained notoriety for defecting to the West and revealing plans for the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

Born Samuel Ginsberg on June 28, 1899, to Jewish parents in Podwołoczyska, Galicia, Austria-Hungary (now Pidvolochysk, Ukraine), Krivitsky adopted his pseudonym, which derived from the Slavic root for “crooked, twisted,” during his time with the Cheka, the Bolshevik security and intelligence service.

Operating under false identities, Krivitsky served as an illegal resident spy across Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Italy, and Hungary.

Rising to the rank of control officer, he orchestrated industrial sabotage, stole plans for submarines and planes, intercepted correspondence between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, and recruited numerous agents, including Magda Lupescu (“Madame Lupescu”) and Noel Field.

In May 1937, Krivitsky was dispatched to The Hague, Netherlands, where he coordinated intelligence operations throughout Western Europe while posing as an antiquarian. He established one of the largest intelligence networks in Western Europe, living with his wife in The Hague.

In 1937, amidst the “Yezhov purges” in Moscow, Krivitsky feared he would suffer the fate of his repressed colleagues. When ordered to return to Moscow, he sought political asylum in France, which was granted.

Moving to the United States in 1938, Krivitsky published critical articles about the USSR and authored the book “I Was Stalin’s Agent,” exposing approximately one hundred individuals collaborating with Soviet intelligence.

He also disclosed the identity of a British cipher operator working for the USSR since 1934 and implicated Kim Philby, a member of the Cambridge Five, though his claims about Philby were initially disregarded by British authorities.

Despite multiple attempts by Soviet intelligence to kidnap him, Krivitsky managed to evade capture, living in constant fear.

However, on February 10, 1941, his body was discovered in a room at the Bellevue Hotel in Washington, D.C., on the day he was scheduled to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee about Soviet agents in the United States.

Found beside his body was a pistol and a suicide note. The FBI ruled his death as suicide, although Krivitsky had repeatedly expressed concerns that his demise could be made to look like suicide.

The Killing of Ex-Navy Captain Using Chloroform-Soaked Headscarf

Another tale from the annals of Cold War intrigue took place in the summer of 1959, when Captain 3rd Rank Nikolai Artamonov, commander of a Soviet destroyer, embarked on a daring escape to Sweden.

The journey to the shores of Scandinavia was fraught with deception, as the captain misled the helmsman-engineman, steering the vessel off course under the guise of being lost.

Seeking asylum in Sweden, Artamonov’s hopes were dashed when he was handed over to the CIA, with whom he pledged cooperation.

Embracing a new identity as Shadrin, he was granted American citizenship and employed by the US Department of Defense intelligence agency, earning a salary commensurate with his naval rank.

In 1965, the KGB tracked down Artamonov and endeavored to recruit him. His wife and son, steadfast in their belief in his heroism, unwittingly aided the KGB’s efforts by negotiating on his behalf, unaware of the unfolding espionage drama.

While Artamonov initially provided valuable intelligence to the KGB in 1968, suspicions arose regarding his sincerity and the veracity of the information he shared.

Though the Chekists, members of the Cheka, the first in the succession of Soviet secret police agencies, harbored doubts, they concealed their distrust.

The plot thickened in 1975 when Artamonov was lured to Austria under the pretense of meeting a successful illegal intelligence officer operating in the United States. However, the rendezvous took a sinister turn as a chloroform-soaked handkerchief rendered Artamonov unconscious.

Intended to be transported to Czechoslovakia, a delay at the border forced the kidnappers to increase the dosage, resulting in a fatal outcome for the former captain. Despite efforts to revive him and bring him to trial, their mission ended in the death of Artamonov.

The Untraceable Toxin Employed In Alexander Litvinenko’s Assassination

Alexander Valterovich Litvinenko, a former Russian FSB officer turned British citizen, was a vocal critic of President Vladimir Putin and coined the term “mafia state” to describe Russia.

In November 1998, Litvinenko and several fellow FSB officers publicly accused their superiors of orchestrating the assassination of Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky.

Subsequently, Litvinenko was arrested in March of the following year on charges related to exceeding the authority of his position.

Though acquitted in November 1999, he was re-arrested, only to have the charges dismissed again in 2000. He fled to the UK in the same year, where he worked as a journalist and consultant for British intelligence.

In 2006, Litvinenko was poisoned with polonium-210, a rare and highly radioactive substance, leading to his death. British authorities, in a subsequent homicide investigation, pinpointed Andrey Lugovoy, a former member of Russia’s Federal Protective Service (FSO), as the main suspect.

Russia declined to extradite Lugovoy, citing constitutional barriers against the extradition of Russian nationals. This stance strained diplomatic ties between Russia and the UK, prompting global scrutiny of Russia’s role in the tragic event.

Salisbury Poisoning Incident

While the Soviet Union and Russia have a history of effectively eliminating individuals they label as traitors, there have been instances where their operations have faced setbacks.

One such case is the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal, famously known as the Salisbury Poisonings, which occurred on March 4, 2018, in Salisbury, England.

Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military officer and double agent for British intelligence agencies, was the target of a botched assassination attempt using a Novichok nerve agent.

Both Sergei and his daughter, Yulia, were hospitalized in critical condition for several weeks before eventually recovering. In response, the British government accused Russia of attempted murder and implemented punitive measures, including the expulsion of Russian diplomats.

This action was supported by 28 other countries, resulting in the unprecedented expulsion of 153 Russian diplomats by the end of March 2018. Russia denied the accusations and retaliated by expelling foreign diplomats while accusing Britain of orchestrating the poisoning.

The Salisbury Poisonings garnered international attention and raised concerns about state-sponsored assassinations on foreign soil.

Also, on June 30, 2018, another poisoning incident unfolded in Amesbury, located seven miles north of Salisbury, involving two British citizens. Charlie Rowley discovered a perfume bottle containing the same nerve agent discarded in Salisbury and passed it on to Dawn Sturgess, who applied it to her wrist.

Sturgess fell ill and tragically died on July 8, while Rowley survived. British authorities believe the incident was not a targeted attack but rather a consequence of the improper disposal of the nerve agent following the Salisbury poisoning.

- Contact the author at ashishmichel(at)gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News